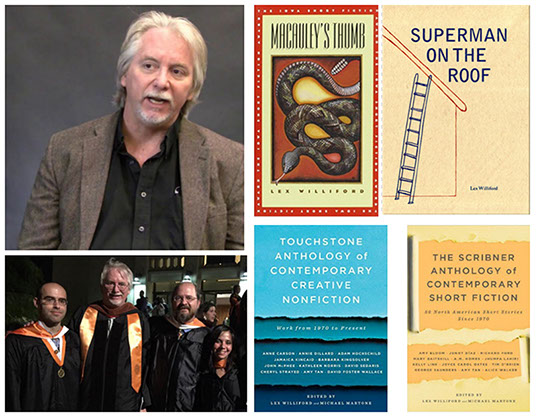

Lex Williford is the founding director of the online MFA at the University of Texas at El Paso and is the current chair of UTEP’s bilingual MFA program. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in American Literary Review, Elm Leaves, Fiction, Glimmer Train Stories, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Kansas Quarterly, Laurel Review, Natural Bridge, The Novel and Short Story Writer’s Market 2002, Poets & Writers, Quarterly West, Prairie Schooner, Shenandoah, Smokelong Quarterly, Southern Review, Sou’wester, StoryQuarterly, Tame me, Virginia Quarterly Review, Water~Stone, and Witness; his stories have been anthologized in Flash Fiction, Sudden Flash Youth, The Iowa Award: The Best Stories, 1991–2000 and The Best of Witness: 1987–2004, The Eloquent Short Story, and elsewhere. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Blue Mountain Center, the Centrum Foundation, the Djerassi Foundation, the MacDowell Colony, the Millay Colony, the Ragdale Foundation, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, Villa Montalvo, the Wurlitzer Foundation and Yaddo. He is coeditor, with Michael Martone, of the popular Scribner Anthology of Contemporary Short Fiction, now in its second edition, and the Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Nonfiction.

7.17.2016 Lex Williford, El Paso writer and teacher, editor

Many of our readers are aspiring writers — but with the day job they can’t find the time or the way to write. In this week’s issue Lone Star Listens visits with Lex Williford, who chairs the online creative writing MFA program at the University of Texas at El Paso. Williford is a prolific short story and short form author himself, and he discusses his writing life along with his academic life that embraces this one-of-a-kind writing program.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: For the past decade you have lived in Texas, heading up the bilingual online MFA in creative writing program at the University of Texas at El Paso. Where did you grow up, and how did that influence your writing?

LEX WILLIFORD: First, let me clarify. Our on-campus MFA program is bilingual, but we have students who are primarily monolingual, in either English or Spanish. Our online MFA program mostly focuses on writing English, though we do have students writing in Spanish at times. I’m teaching a screenwriting class this summer session, and one of the scripts we’re reading is in Spanish—a crossover student from our on-campus program taking an online class.

I was born in El Paso, and I never expected that I might someday return. My father was stationed as a radar commander and a second lieutenant at Fort Bliss in the mid1950s, and I was born at Biggs Air Force Base when the Fort Bliss hospital was dealing with a diphtheria epidemic.

My parents moved me at six months back to Dallas, where I grew up. That place, the place of my childhood, is often the setting of my stories; in many ways that Dallas no longer exists. I remember going to the Plano drive-in when Plano was nothing but farms and cotton fields. Now I drive through the town and there’s nothing plain old about it — skyscrapers left and right for miles — as if I’ve been thrown into a time warp.

I’ve moved all over, taught all over — in Missouri and Arkansas and Alabama and Illinois — and I’ve gone to most of the artist residencies in the northeast and California, so I returned to El Paso as something of a Texas expatriate. It felt like destiny somehow, and it still does. El Paso is a wonderful place to land, such a rich and thriving and diverse and open culture, UTEP a beautiful university with my favorite students ever, eighty percent Mexico or Mexican American.

I feel very much at home here because I was adopted almost immediately, even though I’m just a bland old güero, a blondie. (Actually, my hair’s white because I’m old.) But a lot about Texas baffles me — the open hostility toward people of color, immigrants, etc., especially these days, when the country has become so polarized. Baffled by Texas legislators, who vote to cut state funding for education, then say we should have guns on campus. The whole thing is a little crazy-making sometimes. At the beginning of the twenty-first century I continue to be appalled at how too many white folks act, fearful and hateful and ignorant and too often proud of it. I have many ambivalent feelings about Texas, about the Deep South, though the racism I see in white communities is as widespread in the Midwest and North as it is here. I just don’t understand it. I also feel ambivalence about my family at times, who I write about indirectly, but that doesn’t mean that I don’t love them or the place I grew up. I do, but it’s a complex love, not something I can't explain in any other way than through my stories — most of which aren’t exactly cheerful.

Did you come from a family of storytellers? And when did you know that you wanted to be a writer?

My father, who just turned eighty-five, has been both the inspiration for and something of a subject of my fiction. He was and still is a remarkable storyteller, especially a teller of complex, hilarious jokes. I never learned short jokes—except for the Aggie jokes only he could tell in our house. They were always long jokes, and my father’s theatricality definitely rubbed off on me—and on one of my sisters, who was an actor in New York for many years. I love my father in the same way I love Texas, but it’s a complex love, not without questioning or skepticism. He is. in almost every way that those who might know what I’m talking about, a Texas Aggie who came up in the Corps of Cadets in the fifties. That makes him tough and quite conservative in his beliefs, stubborn in ways that are almost comic. But he can be remarkably kind and generous, and he was a remarkable watercolor artist and architect known for several of his buildings in Dallas, especially Douglas Plaza in Preston Center. The greatest gift he gave me was a love of drawing and painting and art — and storytelling. I was fortunate in that he was so gifted, so generous, so willing to share his gifts.

My father wanted me to be an architect like him, but I decided to write instead. I started with drawing and painting, but the images I paint now are mostly in words.

The audience of Lone Star Literary Life is a real mixed bag — we have people who like to read books about Texas and by Texas authors, but we also have academics, librarians, and publishing industry professionals. However, our audience may not be aware of the various anthologies and literary journals where you have been so successful in getting published. For example, you co-edited two literary anthologies; will you describe them for our readers?

I’ve been incredibly fortunate to co-edit (with Michael Martone, a brilliant, innovative short story writer and teacher I call the Story Laureate of Indiana) two anthologies for Simon & Schuster, one of contemporary creative nonfiction, the other of contemporary short fiction. The idea for the first anthology came to me when I taught with Michael at the University of Alabama. What if, I thought, we polled the great writers and writing teachers all across the U.S. to find out what their favorite contemporary fiction (and later creative nonfiction) was, what they most often teach in their classes? I wrote a book proposal and it was accepted almost right away. Since then, the fiction anthology, now in its second edition, and the creative nonfiction anthology, in its first, both have been more successful than I could have ever imagined. We’ve been talking about going into new editions for both anthologies, but I’m inclined to work on my own writing (and drawing) for now, mostly because the publishing industry has changed so significantly since the first edition of our first anthology in 1999 and because being an editor of such complex projects is incredibly time-consuming and stressful.

Some people have said that the short story is making a comeback, through the variety of short-read formats now available in digital and audiobooks. As someone who has published short stories in some of the nation’s most prestigious journals, what’s your take on the status of short fiction?

Like Frank O’Connor, the great Irish short story writer — the writer of one of my favorite books about short fiction, The Lonely Voice — I think of short fiction as a close cousin to poetry. The very short form I suppose I’m best known for — flash fiction — has been popular since the eighties, when I began writing short-short stories, but it’s always been around, in many forms, the parable and fable as old as storytelling itself. The chapbook that’s coming out is a novella in flash, ten stories no longer than 1,000 words each, which compress time and dramatic incidents into the tightest possible space, fifty years covered in a book of forty pages, which is part of a longer book I’ve been writing for quite a while, and I hope to include these little stories as the layers in a layer cake of longer stories about the same characters. Compression of the kind we’re talking about is, for me, an obsession, and it’s essential to the short story form. For example, to keep all my stories under 1,000 words for this chapbook I had to be selective about what I kept and what I cut. That process forced me add to and then to boil the stories down to their essences, and that exercise is one I’ve learned a tremendous amount about in the practice of being a writer and, I hope, a teacher. I suggest the exercise of compression for my students all the time.

As for the short-story form, it will always thrive, I think. We’ve been in a short-story renaissance since before the rise of writers like Raymond Carver, a period that makes the twenties, the last great renaissance of the short story, look almost short-lived. The proliferation of creative writing programs has something to do with that, and the quality of short stories has just gotten better and better, the bar for the form rising higher and higher. I don’t see that changing, or at least I hope it doesn’t change.

Some of the greatest short story writers ever alive are writing right now: Alice Munro, William Trevor, Charles Baxter, Sherman Alexie, Louise Erdrich, Anthony Doerr, Dagoberto Gilb, Sandra Cisneros, Denis Johnson, Annie Proulx, Junot Díaz, George Sanders, Edward P. Jones, ZZ Packer, Joyce Carol Oates—the list goes on and on. Short stories are a difficult form, and that's what make them appealing to me, the challenges they always present. I’m not by nature a novelist because I try to make each chapter I write have a kind of completeness that makes it stand alone even if it’s part of something longer. For this reason, over the years chapters I’ve written have taken me a long time and often end up being published in places like Glimmer Train Stories. I’ve worked mostly in what we call nowadays “the novel in stories.”

The remarkable short-story writer Joy Williams recently said something that pretty much covers the short-story form for me, what I look for in fiction in general: When she reaches the end of the story, she writes, “I want to be devastated." I love that. I’ve compared the short-short form to cherries, something sweet, lyrical, but also a bit tart and dark, with a seed inside hard enough to break a tooth — or to cherry bombs, little stories that are always in danger of going off in one’s hands. In fact, I have to have that sense of risk and danger. If I’m not terrified when I’m writing, I feel as if I’m just typing.

Your chapbook Superman on the Roof was recently the winner of the Tenth Annual Rose Metal Press Short Short Chapbook Contest, selected by Ira Sukrungruang. For our readers not familiar with that format, will you tell them about the format, and then will you tell us specifically about your book?

I was completely surprised by winning this prize, a prize I’ve used as an excuse to rewrite and rewrite these stories endlessly, throwing out the ones that didn’t work, then writing others. Ira’s introduction to the books is wonderful. He says just what I’d hope someone might say: that every word, every sentence, has a sense of urgency.

First, a little about the publisher: Rose Metal Press specializes in hybrid forms, forms that blur the boundaries between poetry and fiction, prose poetry and flash fiction, etc. It’s a terrific press, with, I’ve learned, two terrific editors, however small the press might be, and I’ve always loved the book of flash fiction exercises Tara Masih put together, The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction. It’s a book every writer of short fiction should buy and read. One of the essays (and one of the stories that shows up in Superman on the Roof) was about the forty days I spent in the desert writing in 2002, a writing assignment I gave myself at the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, New Mexico, to try to write a story every day. I ended up publishing most of those stories, though they were often raw and unfinished when I left Taos. I’ve been working on them ever since.

Second, a little about chapbooks: A short book form usually reserved for poetry, a chapbook is a little book varying in length, often published in limited editions with the kinds of handmade covers and handset type associated with the highest quality small presses, but usually under a hundred pages, and it’s a form particularly well suited to what the editors, Abigail Beckel and Kathleen Rooney, call a novella in flash. Their press is innovative in far too many ways to describe here, but I recommend going to the press’s website just to see the wide variety of books they publish: www.rosemetalpress.com. I believe the print run was 400, and when those chapbooks are gone, that’ll be it.

Many of our readers are aspiring authors, and they’d like to hear a few words of wisdom from the chair of one of the most innovative online creative writing programs in the country. Will you describe your program for us?

Our faculty set out not long after the turn of the century to create a program as distinctive as the place we taught. We began with a bilingual program which we used to attract students from all over the Americas, and those students have done remarkably well, beginning writing programs in their home countries like Colombia, Uruguay, Peru, etc. They’re amazing students, just amazing, and many of them have gone on to win prestigious awards all over the world. Our faculty — we currently have faculty from the U. S., Mexico, Colombia, Cuba, Peru, the Philippines, etc., including some of the most respected translators and chican@ writers in the U.S. The first Hispanic writer ever to win the prestigious PEN/Faulkner award was our own Benjamin Alíre Säenz, who just retired last spring.

Around ten years ago, the UT Telecampus recruited us to begin the first online MFA in the country. We thought it was the ideal way of getting students from the Americas to the U.S. post–9/11, when so many students were having trouble getting student visas. The program has grown to around sixty students, and they’re as talented as any MFA students I’ve ever taught. I was skeptical that an online MFA would be possible, but our students have surprised us year after year, many of them going on to distinguished careers. Unfortunately, because of budget cuts, the UT Telecampus went bust, and we had to scramble to find a way to keep our online MFA alive, which I’m proud to say we managed, especially with the help of our current director, novelist and short-story writer Daniel Chacón.

What Texas authors do you enjoy reading?

Katherine Anne Porter — good god, what a remarkable short story writer she was — and, of course, Larry McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy. But there are others I know many of your readers may not have heard of, like Allen Weir, whose eight-hundred-page novel Tejano (SMU Press), is remarkable. And, of course, we have terrific Mexican-American writers like Dagoberto Gilb and Sandra Cisneros. What’s happening in the literatures of the Americas, in the writing by people of color, is absolutely amazing. People who’ve historically been silenced, invisible, have created a remarkable chorus of voices which says everything important about what it means to be an American, hyphenated or not. Writers of color have crossed the artificial borders between languages and cultures in ways we should find pride in as Americans. Forget the culture wars. When it comes to the diversity of voices in contemporary American literature, we should all feel joy, hopeful, at peace.

What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

Be stubborn and persistent, and don’t give up. Do the work for its own sake alone. Forget money or fame. Work your ass off. The Mexicano mystery writer Paco Taibo once said when visiting the UTEP campus that the most important thing for any writer is “tiempo de nalgas.” Ass time. Putting your ass in a chair and staying there until something comes. It’s not as much about talent as it is about learning craft and practicing, day after day. Shouldering the boulder, I call it, like Sisyphus, knowing that that big stone is probably going to roll back down the hill but pushing and pushing anyway, then walking back down the hill and pushing again. You have to push for the muse to visit. She’s generous when she sees us sweating a little.

I understand that you have a couple of novels in the works. Can you talk about those?

I’ve been working for too many years on two novels, and I still have a lot of work to do to get either of them finished. I’m slow, and I’ve stopped apologizing for being slow, even glacial. I’ve stopped hating how I work, too. I just work. And I’ve stopped talking about my work until it’s done. All I can say is that both novels occur in Texas — one set mostly in east Texas and the other in central Texas — but that’s as far as I’ll go.

What’s next for Lex Williford?

Last year, I received a grant to illustrate a kids’ book I wrote and sketched years ago. I’ve been working on that mostly, and I’ve found that drawing and writing seem to feed each other. I hope to get that book done in a year or so. And I’ve written and rewritten a couple of scripts that have gotten me a little notice, but I’m not happy with either of them. I plan to rewrite them again, from the ground up, if I can ever find the time. Being chair has taken more of my time than I’m willing to admit, but I’ve learned a lot doing it. I’ll be happy to go back to the classroom full time, though. I’m a lousy administrator. I’m a teaching writer and a writing teacher. The two things feed each other in ways I can’t begin to describe. I love teaching. My students have taught me more than I’ve ever taught them. I’m incredibly lucky in that way. And I started a family — not a second but a first — in my mid-fifties, have two terrific kids six and eight who keep me young, who teach me and do their best to keep me humble. And my wife, she’s just amazing. I make no predictions because, for me, the work is its own reward.

* * * * *