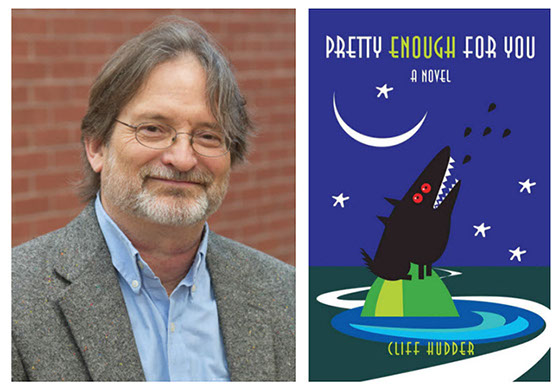

Pretty Enough for You has been described as a rollicking carnival of a debut novel for Cliff Hudder. It’s the kind of book that reminds you that literary fiction can be fun, so it seems only fitting that its author is our final front-page profile of the year, as we look back and forward at the same time.

With Conroe novelist Hudder, Lone Star Lit has now interviewed all ten authors of our Top Fiction of 2015 list.Hudder, who teaches English at Lone Star College-Montgomery, took time between semesters for an email interview with us.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Where did you grow up, Cliff, and would you describe that for us?

CLIFF HUDDER: I grew up in Pasadena, Texas, a refinery town on Houston’s southeast flank. Back then, the 1960s and ’70’s, Houston radio stations commonly used Pasadena as the punch line for jokes about rural country redneck hicks, but those are our chemical plants you see John Travolta’s pickup driving past in the opening credits of Urban Cowboy. The sinful megalopolis where the poor lad brings his inadequate cowboy values is actually Pasadena, not Houston.

In my youth it was lily-white and ultra conservative in addition to being carcinogenic. The schools were quite good, though — Mrs. Bowen had us reading Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and Thornton Wilder as high school freshmen — but I met exactly one Latino and no black people in my classes. On Red Bluff Road was a low red brick building that served as regional Klan Headquarters, and I don’t mean secret headquarters: a sign on the roof spelled out KNIGHTS OF THE KU KLUX KLAN in red letters five feet tall. I grew up thinking every town had a branch office.

Of course, several decades ago the building was sold and the sign replaced by five-foot red letters that spelled out HERNANDEZ UPHOLSTERY, and the area is now largely Hispanic. Unlike some Texas writers I don’t look back with nostalgia to my small-town youth and despair of the changes. After college I moved and spent about twenty years in the Montrose area of Houston — not far from Pasadena in miles, but pretty distant otherwise — and I still consider that my spiritual homeland, though I spend my days now here behind the Pine Curtain in Montgomery County.

Was there anyone you knew and remember in particular from your youth that was a great storyteller, and how did they influence you?

That’s an interesting question because I was kind of a nerdy only child who stayed indoors reading comic books and building models most of the time, and I appear to have just spent a good paragraph bad-mouthing my hometown, but in fact I was surrounded by wonderful working-class East Texas and Cajun families, and the parents especially were all terrific storytellers. My dad liked to entertain, and I couldn’t get enough of hanging out and listening to the grownups, especially around the cocktail hour. In addition to great stories, they had a way with language and turns of phrase, and were big gossips. Everything was high stakes. A close friend of our family would give me dating advice like: “Stay away from her, Cliffie. That girl will kill you so fast it’ll make your head spin.” I loved that imagery. I’m not just going to be betrayed, I’m going to die, and be so surprised my head will still be spinning in the next world! They constructed elaborate curses as well that I won’t go into, plus malapropisms. The people in my neighborhood complained about being misunderestimated long before George W. came along. So typical, I’ve griped about their narrow-mindedness above, and now you’re making me miss them.

As you were making your way in the world you switched from pursuing a law degree to an MFA. What drove that decision?

It’s hard to think of it as a “switch” because it happened over the course of a decade. I had an anthropology degree and what can you do with that but go to law school? There they talked a lot about “learning to love the law,” but that never happened for me: in fact the opposite. I left after a semester and a half, got interested in film, took classes in filmmaking at the University of Houston, and even sold popcorn at the Greenway Theater for a while so I could watch free foreign movies. Then I got hired on at an audio-visual production company where we made corporate and industrial films (“Advanced Barge Tankerman Navigation,” “This Is Your Sump Pump,” etc. . . . ), and working there I became interested in still photography so did that for a while.

But I’d been thinking about writing the whole time, and I’d always been a big reader. When I divorced my first wife in 1991 I felt adrift, without responsibilities, and thought: “If there’s something you’d really like to do this would be a good time.” I took some fiction writing classes at the University of Houston, where, because of the creative writing program, mere citizens could sign up for undergraduate classes with excellent writers like Robert Cohen and Glenn Blake. I started publishing stories in small journals, and after a while the program admitted me. I guess it was based on the stories I wrote because I badly bombed the GRE Subject Exam: I knew next to nothing about the critical study of literature. Getting that MFA was like nothing I’d done before, and was a pivotal experience in my life.

Pretty Enough for You is your debut novel. For people who haven’t yet read it, would you describe it for them?

I usually say to people that it’s a re-telling — or better a mis-telling — of Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, set as a contemporary office romance in a Houston law firm. There’s a triangle involving a passionate young Hester-type, a Dimmesdale-like milquetoast she loves, and a manipulative jerk who wants to make them both miserable. When I stumbled across the idea of letting the Chillingworth character narrate the thing it started to come together. I’m not totally sure any of the Hawthorne connection is obvious in the final product (maybe in a certain letter of the alphabet featured on the heroine’s tramp stamp). The narrator is a mess, a product of the “bad choices make good stories” school of fiction writing, so it’s also about his responsibilities — especially when it comes to caring for his autistic son—and how he balances those against his tawdry, self-destructive desires. Or fails to.

In other interviews you have mentioned that Kurt Vonnegut was an influence. (I can see that.) Which Texas authors do you appreciate?

That to me is such a dangerous question because I am a partisan promoter of Texas authors. I have writer friends who don’t like that Texas label as they feel it limits their readership — and they’ve got a good point — but I’ve decided to embrace it. The late Tom Pilkington at Tarleton State felt our state’s writing is poised to come into its own, achieve a renaissance, as American literature did in the mid-nineteenth century, and I’ve decided to believe that, too. (Why else set The Scarlet Letter in a Houston law firm?) The dissertation I’m working on presently at Texas A&M concerns Houston writers, and I teach a class at Lone Star College–Montgomery called “Writing About Texas Film and Literature,” so I have many favorites.

Now, that sermon being over: there are twentieth-century greats I appreciate like Billy Lee Brammer, the early Larry McMurtry, Katherine Anne Porter, Elmer Kelton, Bud Shrake, William Goyen, Tómas Rivera, and Américo Paredes. More current authors include Ben Fountain, Benjamin Sáenz, Farnoosh Moshiri, Dagoberto Gilb, and Sandra Cisneros.

Then, because I’m program director for the “Writers in Performance” monthly reading series our college hosts in partnership with the Montgomery County Literary Arts Council, I’ve been fortunate to actually meet quite a few Texas writers I admire a lot: Rick Bass, Stephen Harrigan, Elizabeth Crook, Wendell Mayo, Bruce Machart, Jim Sanderson, Lowell Mick White, and more. All of the series writers meet with my students, too, so I get to eavesdrop and learn new things constantly.

I’ve been reading Sarah Bird for a while and got to meet her last year when she visited the series: her most recent, Above the East China Sea, is so awesome. Nan Cuba’s Body and Bread is very unusual, “unusual” being my highest mark of praise when it comes to books. I got to meet Rolando Hinojosa-Smith a few years back; the Klail City Death Trip series is very important to me. A friend of mine is San Antonio native David Samuel Levinson, who lives now in Brooklyn, New York, but I insist to his dismay he’s still a Texas writer. We look over each other’s manuscripts—he’s great at asking the hard questions like “Why am I reading this?”—and he has something coming out soon that will knock America on its behind. I’ve got Antonio Ruiz-Comacho’s Barefoot Dogs on the nightstand at this moment and like it a lot.

See what I mean? Is there space to mention poets? I’ll just make a quick start with Larry Thomas, Sarah Cortez, Carmen Tafolla, and David Parsons. Dave is the 2011 Texas poet laureate, my partner in producing the reading series, and is a great poet, good friend, and the reason I’ve kept writing for the past fifteen years — writing more than comments on student essays, that is.

How has publishing changed since you began writing?

All of my works have appeared in specialized literary journals or come from small, independent, or university presses, like Sam Houston State’s Texas Review Press for Pretty Enough for You. Sadly, such presses are under constant pressure from economic forces, and some fine ones in Texas have gone under or drastically cut back their yearly titles. I don’t know that their approach has changed, as they’re still full of dedicated people, like Paul Ruffin at TRP, who publish what they believe in and often lose money doing so.

The growth in technologies like Kindle and other eBook platforms is worth noting; conceivably that could help with small-press production and distribution costs. Other aspects of publishing have really overturned, like the self-publishing explosion. I’m not sure what to make of that. I have friends who have had both good and bad experiences with larger, national commercial houses. It does seem with those imprints these days that if your work doesn’t show ultra-fast success, your book is in danger of disappearing. Meanwhile, every writer I know has had to invest more time personally in marketing, no matter who publishes their work. The landscape is shifting, but I’m hoping small and university presses will find a way of holding onto their niche into the future.

One thing that hasn’t changed is that if you worry too much about publishing, you’ll never find time to write.

What’s your writing process like?

I’d love to say I write every day with great discipline but in fact I am too busy for that, so I have to clear space to go on productive binges. I write different kinds of things, but my approach is pretty much the same. There comes a time after pondering, note-taking, head-scratching, and researching that I go spatial. I arrange the paper scraps, sketches, legal pads and bev naps on some flat surface and start to sequence. There’s a teaching theater on our campus with twenty tables and I’ve been known to use them all. I knit together a rough draft, then start to pare, polish, and re-arrange.

I recently tried to learn how to play chess, and I’ve concluded that I’ll never get it because it requires thinking ahead. I need everything to be out there already, all at once, and then I can start to sculpt away at it, seek the pattern, sometimes weave threads backwards into the narrative fabric. And, of course, I’m open to change during the process. It’s the surprises that are most gratifying when writing: the connections you didn’t see when you started, the characters who climb up out of nowhere and do the damndest things you never expected. Keeping in mind the possibility of such wonders allays the drudgery of drafting.

As an academic, can you give us your take on the question of “Can writing be taught?”

The first thing I tell my fiction-writing students is that I can’t teach them to write. A student who is now a good friend, Diane Logan, still tells about how this almost made her walk out the first day and demand her money back. Like many academics, I do think writing can be learned, but the responsibility on the writer herself is high: there’s no list of menu items I can hand over that will insure the production of a good story.

Having said that, the conventions of good storytelling can be both taught and learned, and should be: something stressed by my mentor at UH, Daniel Stern. But that’s different and has to do with the level of seriousness you’re willing to undertake to work in this art form; understanding the “laws” so you can break them on purpose if the story demands is one way of looking at it. But you can know about plot, character, and point of view forwards and backwards and that alone won’t ensure a good story, no matter what Writer’s Digest tells you.

I took a workshop recently with Angie Cruz at A&M (taking one after teaching them for many years is quite weird), and she feels writing is a state of being, more about what you are than what you know. I’ve been mulling that over and am starting to believe it. You don’t have to enroll in writing workshops to learn to write, but as an academic I will throw in that if you’re in the Houston area there are so many high-quality writers in the various schools, plus resources like Inprint, Inc., that I always say you’ve got nothing to lose giving them a try.

A workshop probably can’t help or harm a good writer, but writing requires a long apprenticeship and there are other intangible advantages to joining a community of people who take what you do seriously, and who are trying to do the same thing themselves. If you’re lucky you might also uncover a deeper way of reading: one of the gifts I received from my MFA.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned from the experience of putting a debut novel out in the world?

I’ve learned how hard it is to find readers. Especially serious readers who will then give you some kind of feedback or come and sit down and talk with you, or take a minute and put some stars on Amazon, or anything. I do have some people like that and treasure them a lot, but . . . maybe I expected masses hungry for fiction to materialize after the book appeared—some kind of magic caused by publication? It’s partly that the society we live in doesn’t value reading much, or maybe it’s just an artifact of how many books there are out there vying for attention, or a result of all the other distractions there are in everyday life . . . or maybe the book really sucks and offends (very possible) but I want to know. To find out what people think about the thing, I’ve sunk big parts of my days into trying to drum up attention for it, but then it’s like waiting by the phone for that important call. I’ve come to think that this is the greatest desire of writers and I’ve heard it from more than one: we want readers, and they are hard to find.

One final question. If you could give aspiring authors one piece of advice, what would it be?

There’s so much advice on writing flying around out there, and my students will assure you I’m full of it. Here’s something I’ve been pondering. Recently we had the poet, critic, and novelist Reginald Gibbons at our reading series, and he said the thing he’s trying most to get his students and aspiring writers to do is just loosen up. As in: don’t be afraid of what someone is going to think of you when they read your work; don’t self-edit or pre-censor out of worry; be honest and write the world you see. I like that a lot, as it seems to speak to so many other issues.

Loosen up. So simple. So not easy.

* * * * *