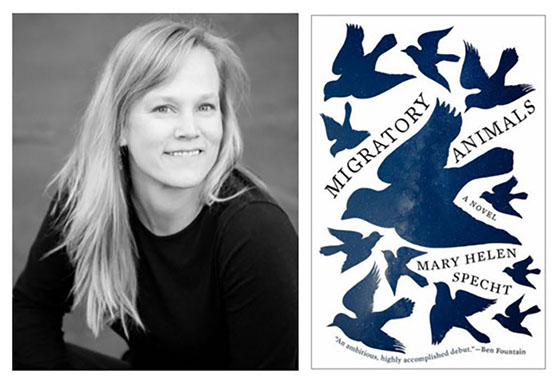

Born and raised in Abilene, Texas, Mary Helen Specht has a B.A. in English from Rice University and an M.F.A. in creative writing from Emerson College, where she won the department’s fiction award. Her writing has been nominated for multiple Pushcart Prizes and has appeared in numerous publications, including The New York Times, The Colorado Review, Prairie Schooner, Michigan Quarterly Review, The Southwest Review, Florida Review, Southwestern American Literature, World Literature Today, Blue Mesa, Hunger Mountain, Bookslut, The Texas Observer, and Night Train, where she won the Richard Yates Short Story Award.

A past Fulbright Scholar to Nigeria and Dobie-Paisano Writing Fellow, Specht teaches creative writing at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas.

Her first novel, Migratory Animals, was published by Harper Perennial in January 2015.

“Migratory Animals brings to the page an astonishing admixture of ambitiousness, originality, and authority that’s rare among established writers and exceptional for a first effort. . . . Richly layered and psychologically incisive, it is that rare first novel that leaves the reader clamoring for the next.” —Boston Globe

“Delightfully ambitious. . . . Specht perfectly captures the minute details of contemporary life in a certain social niche. . . . Novels of such scope and ambition, inspecting the way we encounter the wider world today, are rare.” —Joanna Rakoff, New York Times Book Review

“Specht’s strong, nuanced prose reveals heartfelt insights into her bevy of characters, ensuring a memorable and touching read.” —Texas Observer

“A promising debut. . . . One of the novel’s wonders is the way Specht illustrates her characters — not with great globs of exposition, but with quick, economical brushstrokes.” —Dallas Morning News

“A memorable novel. . . . The characters represent a specific place and a specific era, but their travails and truths are universal and timeless.” —San Antonio Express-News

“A finely wrought first novel. . . . Specht weaves fascinating details on snowflakes, weaving, birding, genetics and engineering, plus a spot-on-portrait of Austin.” —Kirkus

“Specht’s vivid debut probes the nature of family, the notion of home, and the tender burdens of both. . . . Specht’s distinctive prose — rich with sharp observations, nimble language, and lyrical imagery — makes the novel a quirky and memorable read.” —Publishers Weekly

12.6.2015

Mary Helen Specht: Exploring the “post-western” Texas

It’s been a banner year for Austin-based author Mary Helen Specht. Her debut novel, Migratory Animals, was published in January and has been welcomed into the world with praise. Here’s just a smattering of the bookish bouquets—a January iBook Selection; a February Indie Next Selection; a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice; and on and on. She was named one of the Ten Authors to Watch by Texas Monthly, was selected as a keynoter at the West Texas Book Festival in her hometown of Abilene, and was invited to appear at the Texas Book Festival.

We were pleased that we were able to interview her via email for this story.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Congratulations on an amazing year, Mary, and an amazing debut novel with Migratory Animals. But you've been quite workmanlike toward this goal, continually publishing short stories and essays — and winning awards — along the way. When did you officially “become a writer,” and how long have you been pursuing the craft?

MARY HELEN SPECHT: Thank you! It has been a great and wild year.

I first became serious about writing fiction in college, and spent about ten years during and after college writing short stories. One of the reasons I transitioned from short stories to the novel form was that I wanted to more fully explore how multiple lives intertwine and affect each other over time, to broaden my canvas, so to speak.

My first tattoo—inked on my eighteenth birthday during a trip to Austin—was of a stylized turtle, which, randomly chosen at the time, turned out to be appropriate. I am certainly the tortoise, not the hare. I revise a lot; I make a lot of mistakes; and I don’t give up.

What made you decide to be a writer? Was there an experience or a series of events that you can define as a turning point toward that path?

While I loved to read growing up—in fact, I sat in the living room with my parents pretending to read Tropic of Cancer long before I actually could—books made me want to live within them rather than to write them. I wanted to be Meg Murry in A Wrinkle in Time, playing with Bunsen burners after school and saving my father from the tesseract. Carl Sagan’s Contact inspired me to subscribe to Astronomy magazine (until I learned you had to be plausible at math to become an actual astronomer); after reading A Separate Peace, I dressed like a boy and begged to enroll in a bucolic boarding school out east. Growing up in a small town in West Texas, books were my wormholes to the wider world.

I’m not sure I can pinpoint one moment where I decided to write stories rather than just imagine myself inside them. It was a gradual process. We probably only get to live one life (boo!); writing fiction allows me, for a time, to embody what it’s like to be someone else born into a different context, with different desires and challenges. I think that’s ultimately why I decided to write.

You grew up in Abilene. What was that experience like, and how does it inform your writing?

While I look back at Abilene with great fondness—all those empty horizons of West Texas and empty hours of youth—like most teenagers, I couldn’t wait to get out. Hometown in the rearview mirror, and all of that. When I left Texas in my early twenties, I didn’t think I’d ever live here again. But like in the Godfather: “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.” Of course, some people would claim that Austin, where I live now, isn’t Texas in the same way that Abilene is.

I have tried to write short stories set in Abilene many times. They never worked, which is strange to me because there are so many rich and interesting contradictions in that town that would make for great fiction. Maybe, even though I haven’t lived there since high school, I’m still too close to be able to see it clearly. In Migratory Animals I did manage to write about Abilene a little. While most of the novel is set in Austin and Nigeria, two of the characters, Flannery and Molly, are sisters who grew up in Abilene, so there are a few sections that flash back to their youth.

Even if most of my fiction isn’t set in Abilene, growing up there certainly informs my work. Almost everything I write explores what I like to think of as a “post-western” Texas, a place where characters try to piece together an identity amongst the remnants of what Texas used to be (and is still known for in the rest of the world). Ranches have become pleasure or retirement spots, and neon longhorn saloons tourist traps; a peculiar brand of Austinesque Texas mythology has gained strength; in small West Texas towns like Abilene, kids are more likely to be in a heavy metal band than know how to ride a horse, even though the idea of themselves as cowboys still holds a powerful authority.

What authors did you grow up reading? Were there Texas authors that come to mind?

My parents are both librarians, so I was raised among books. I used to walk to my father’s library after school and read until he got off work. (Sometimes I would also stand in front of the enormous open dictionary on the mezzanine and look up dirty words.) But as a young person, I was looking for books to take me out of Texas, not further inside it. The writers who were influential to me in high school and college included Virginia Woolf, Michael Ondaatje, Zora Neal Hurston, Marilynne Robinson, Toni Morrison, Alice Munro.

I’m reminded of what Larry McMurtry said: he read himself out of the culture growing up only to read himself back in as an adult. It wasn’t really until I moved to Boston in my twenties that I began reading Texas writers like Katherine Anne Porter and Stephen Harrigan and Sandra Cisneros and even Larry McMurtry himself. In addition to the ones listed above, many other Texas writers have since shaped both my writing and sense of place—including A.C. Greene, J. Frank Dobie, Pat LittleDog, Laura Furman, Sarah Bird, Oscar Casares, and Bret Anthony Johnston, to name just a few.

You were a Fulbright scholar to Nigeria. How did that come about, and how would you describe that experience?

After I finished graduate school in Boston, I was lucky enough to get a creative writing Fulbright grant to Nigeria to study West African fiction. Living there was one of the most beautiful and profound experiences of my life.

One of my areas of research in Nigeria was the literary representation of Africa by westerners. So, I was very aware of (sometimes paralyzed by) the pitfalls that come with writing about a historically marginalized country (which is not to say that I managed to avoid all these pitfalls). In my work I didn't want to portray Nigeria one-dimensionally, when in reality it’s a country with both rural huts and gleaming modern houses, villages without running water and complex concrete flyovers. I wanted to be true to the ways in which Nigeria is unique while avoiding reinforcing stereotypes.

While I didn’t begin writing Migratory Animals until I returned, I brought back notebooks filled with descriptions, which I later combed for the details and images I thought would do the most work in illustrating this complexity. For example, in the prologue, there is a description of a woman wearing a traditional West African wrap while carrying a brand-new computer monitor on her head across the university campus.

How did the process of publication occur for Migratory Animals?

When I returned from Nigeria, I allowed people in the publishing industry to convince me that a memoir of my time living in Nigeria would be more marketable than a novel. I tried that for a while and did end up with a few essays I’m proud of, but, ultimately, I was more interested in writing about what if than what was. I’d left Nigeria, but what if I were a different sort of person and had stayed? What if there was an American scientist who felt she’d finally found love and a home in West Africa but wasn’t allowed to stay? I decided to write the book I wanted to write. When I finished (years later), I found an agent who loved the work for what it was, and she eventually sold it to an arm of HarperCollins.

At thirty-six, you're a member of Generation X. How do the topics of your generation vary from the Baby Boomers, which in some ways is the passing of the guard?

I am a proud GenX-er, and I believe that we see and write about the world with more disillusionment. My generation, like the Boomers, was raised to expect adult lives at least as successful as those of our parents. However, in real economic terms, that hasn’t been the case for most folks.

Migratory Animals is set during the most recent recession. I was particularly drawn to the stories of people I knew who were second-generation immigrants and had been taught that graduating from a good college with a good education was all that was needed to propel themselves into the middle class. The recession highlighted how the system is still rigged in favor of the privileged, and I tried to explore some of that through the characters of Santiago and Brandon.

The character of Alyce developed from my interest and observations concerning the culture of contemporary motherhood; she struggles with connecting emotionally with her children, which is something not really viewed as permissible in our society. The child-mother bond is mythologized as something natural and automatic, a bolt of lightning that hits every woman when she first sees her baby, though in reality this isn’t necessarily the case.

You teach writing at a university. How are your students different from, and similar to, your generation of writers?

In most ways, my students are like all other young, aspiring writers from any generation: they are sometimes shockingly talented, but almost always need to learn to control that talent, to hone the skills necessary to fully wrestle their stories onto the page and ultimately—gasp—revise them. They are often more prepared and resilient than I was at their age. The writer Elizabeth McCracken visited my advanced fiction workshop last year and made the excellent point that while one’s craft may improve over a lifetime, there are certain stories one is only able to access when young. I realized how true that is, and how I have the privilege to watch those stories happen each semester. My students are constantly surprising me with their insights, with the way they see the world with their raw, young person eyes.

Really, the biggest difference I see between their generation of writers and mine—and this is going to come as a surprise to nobody reading this—is how enmeshed my students are with technology. This isn’t always a bad thing—some of my creative nonfiction students recently created really cool experimental essays using platforms like Snapchat and Pinterest, for example. However, technology can also separate them from the world in a way that is not good for aspiring writers. Writers need to be able to observe the pornography of detail around them, to ride a bus and eavesdrop on the conversations, to daydream while walking through campus, and sometimes be totally, absolutely bored out of their minds. Having sound constantly piped into your ears or having access to immediate distraction on your phone, well, those things don’t encourage a full participation in the world around you.

What is your writing process like?

I’ve heard that Colum McCann claims that writing a novel is like getting a four-year degree, and while that may be an exaggeration, for my novel I did have to research—by way of personal interviews, hands-on lessons, and lots and lots of books from the library—the art of weaving, climate science, architecture, Huntington’s Disease, and snowflakes.

In graduate school, one professor encouraged us to take advantage of our characters’ jobs, those concrete details and functions that make up their lives. This transformed my writing practice. Over time I’ve realized that I’m the opposite of a method actor; I work from the outside in. Only after understanding what they do with their hands, with their days, can I begin to access my characters’ inner lives. So, my early drafts begin with the outside world and then slowly move inward.

I don’t outline. I keep piles of notebooks and scraps with ideas and reminders all over my desk that I flip through as I write a first or second draft. I play it pretty fast and loose early on. It’s only after I get to know my characters that I’m able to follow them into a plot. Then, I will try to organize the chapters in a more methodical way. Sometimes I have a beginning and ending, but nothing about how I’ll get from one point to the other. Most of the interesting stuff, for me, comes during the revision process. In terms of rituals, cliché or not, I have to admit that I work better with a cat on my lap.

Are you working on your next novel and can you share with us any insights about it?

Well, it’s still in the playful, exploratory stage so I don’t want to say too much. Right now it’s set in New Mexico in the 1970s. It’s told from the point-of-view of a young man who has become the assistant, promoter, and protégé of a famous painter at the end of her career. The book explores how the narrator (and each of us, to a degree) must come to terms with mediocrity in the face of greatness.

* * * * *