Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

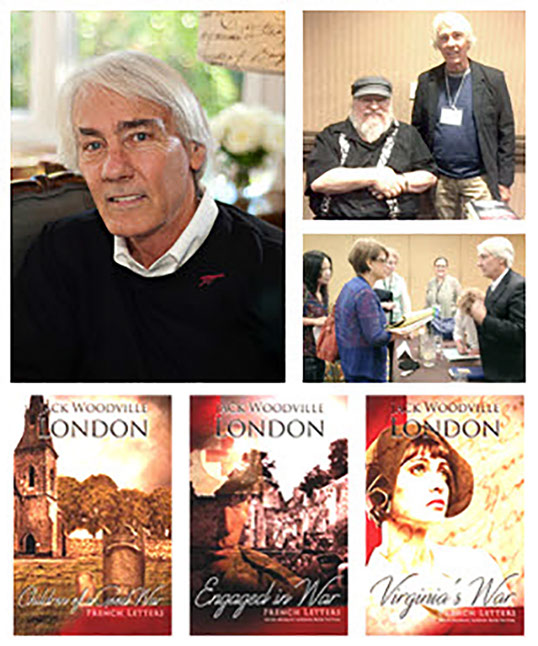

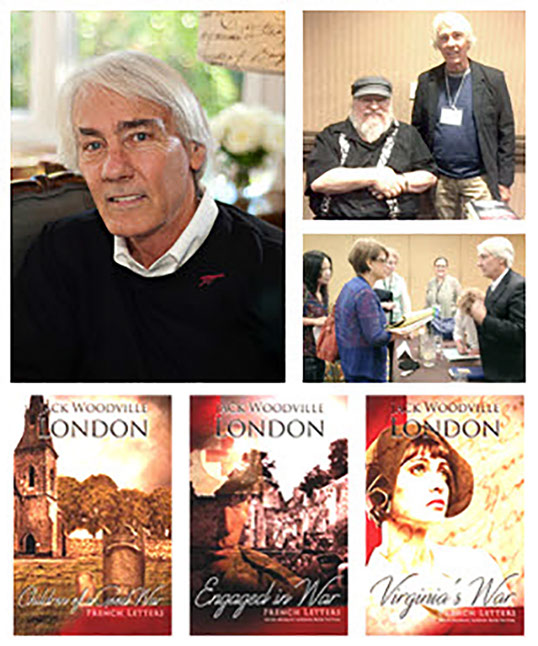

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jack Woodville London studied the craft of fiction at the Academy of Fiction, St. Céré, France, and at Oxford University. He was the first Author of the Year of the Military Writers Society of America. His French Letters novels depict the U.S. in the 1940s, both at home and in the Second World War. Children of a Good War, published November 8, 2018, is the third book in that series. The first book, Virginia’s War, was a finalist for Best Novel of the South and the Dear Author ‘Novel with a Romantic Element’ contest. The second volume, Engaged in War, won the silver medal for general fiction at the London Book Festival. He lives in Austin. www.jwlbooks.com

11.11.2018 London's calling: Austin author pens third novel in World War II historical series

This Veterans’ Day weekend Lone Star Literary Life travels very far from Texas. In fact, our thoughts will be at the Meuse-Argonne American Military Cemetery in eastern France, where featured authorJack Woodville London will be participating in a ceremony to honor an uncle who served in World War I. London has made a career writing about the Greatest Generation who served in World War II. He has told the stories of the boys who left the Texas farms, ranches, town and cities in his French Letters series of novels.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: This is Veterans’ Day weekend, Jack, and you seem like the perfect author for us to feature today. As a matter of fact, while we’re corresponding, you are in France. Can you tell us why?

JACK WOODVILLE LONDON: On November 11, I will be at the Meuse-Argonne American Military Cemetery in Eastern France, as part of the memorial service to honor those who died in World War I. That day is the 100th anniversary of the end of that war. It is the largest American military cemetery in Europe, with over 14,000 American soldiers buried there who died in WW1, almost all of them in the last six weeks of the war. There are in total some 46,000 American men and women who died in World War I who are buried there and elsewhere in France and Belgium.

I will do a reading at the service and also will place flags on the grave of my uncle, who was killed on his first day in battle in 1918, and on the graves of a number of other men whose graves I’ve been asked to locate and to honor.

And I will write about the experience.

You grew up in Groom, Texas (which is a very long way from France). How would you describe your early days?

Groom is the kind of town where people should want their children to grow up, so small that everyone knows everyone, so industrious that kids were expected to have jobs on farms or gas stations or the like from age 10 or 12 onward, and the kind of town where if you didn’t want people to know what you were doing, you better not do it. My father was a bit restless, so we often found ourselves whisked off to Colorado or to a nearby farm or ranch for quail shooting, hay baling, wild fruit picking, and on rare occasions, to California, where some of my aunts and uncles had moved in the Depression or World War II. So it was impressed on me that I had to work hard, that the world is a large and varied and often beautiful place, and that there are all kinds of people in it, not all good.

Did you always want to be a writer? Can you describe for us your first experience in getting published?

I think yes, I did. I took pleasure in writing from being taught by one particular high school teacher, and I am still in love with how the choices of words and ideas can change things.

My first experience in being published was like watching a bicycle race in person: a lot of preparation, a lot of prayer and hard work, a lot of frustration, then it gets close, then you get published, then ffffttt! It moves past you in a blur.

Tell us about your latest novel, Children of a Good War.

Set in 1986, it is the novel of two brothers who, like Cain and Abel, have decided they detest one another from childhood. All of us know, or think we know, who our parents are but rarely do we know who they used to be. In this case a cache of their parents’ wartime letters is unearthed that prove that one of the brothers is not actually a brother, but instead was a child that Dad brought back from the war in France as a baby, perhaps to punish Mom for having an affair while he was away. He first sets to France out to track his father’s wartime steps in order to find out who his real mother is, a journey that makes him discover his parents’ buried secrets and, in the course of things, to find out for himself who he really is.

You do a lot of work with veterans, and you teach writing to vets. What’s that experience been like for you?

Each vet has a story to tell. They might wish to tell it to an audience, or a family, or to the reading world, and often it is a story they want to be able to tell out loud, to themselves, just to get the words out. Almost invariably, they don’t have experience in such things as how to construct a story arc, or how to create characters who seem like people we might know ourselves and conflicts that may seem like the same situations we have been in or, worse, fear being in. So, we concentrate on practicing those kinds of things and learning what they come out like on the written page. It is its own reward.

Like many authors, you are an attorney. How do the two pursuits complement each other?

Attorneys are, or should be, good storytellers. I hope that to that trait I also brought the sense that I learned how to unearth things from people that they would rather I didn’t ask, and how to do research for the background and context of almost any problem, whether it be a murder, a lie, a battle, or a telegram written fifty years ago. Almost all courtroom lawyering involves intense research, learning a new trade (how to be a neurosurgeon in twenty-four hours, then a truck driver . . .), and learning how to weave it into a story that is put on through characters called witnesses.

And, good writers need to learn how to lay down clues and false trails, and how to develop a sense in the reader of being present in the story as it unfolds.

In addition to being an author and attorney, you are a well-regarded historian. How much time do you put into researching one of your books?

I think it would not be far off to say that 50 to 75 per cent of my work surfaces in the form of something I put together in research, whether it is the art work on a 1943 ration card, the way the doors open on a landing craft, the form of address used in old letters, or such unnoticeable things as how sidewalks were built and what went into cake recipes.

But I don’t think those things are “history,” which in my view is not so much what happened on a given day or what did certain people do then as much as why did that thing happen, why did they do it, and what came from the thing having happened or having been done. History, in my view, is a flowing river that has a lot of artifacts to mark the way, such as art work on a ration card or how landing craft doors open. History is not so much the artifacts as the unspoken elephant in the room and often the room itself.

What’s your writing routine and/or creative process like?

I wonder if it is like a drug? When you are in the creative flow it is like a surge of wonderful dopamines, like serotonin. I prefer to write in the morning and use the rest of my work day in research, or the administrative things that have to be dealt with. I encourage writers to seek 1000 words a day, and I try to do that.

Are you working on something new?

Oh, yeah.

What’s on your nightstand to be read?

At the moment I’m reading Code Girls, a history of the American women who developed cryptanalysis in the 1930s and broke the Japanese military and diplomatic codes. I just finished a Hilary Mantel novel titled O’Brian the Giant. I have a stack of books on my desk that have to do with the events of Texas as a republic during the period 1836 to 1846, but to say more would be to say too much.

* * * * *

Praise for Jack Woodville London's FRENCH LETTERS

“I was hooked from the prologue. This is one version of ‘the homefront’ that I’ve never seen before.”

—Dear Author Reviews

“With this trilogy, the author set out to honor his father, a member of the often-silent Greatest Generation and their experiences in the ETO. He has a sure touch when it comes to revitalizing the small stories and furtive gestures of a long-gone society.”

—Military Society Writers of America

“A riveting read of the morality and loyalties of war, French Letters will prove to be a highly entertaining . . . for those who enjoy war fiction.” —Midwest Book Review

* * * * *