Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Michelle Newby Lancaster is a reviewer for Kirkus Reviews and Foreword Reviews, writer, blogger at TexasBookLover.com, and a moderator for the Texas Book Festival. Her reviews appear in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, Concho River Review, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, The Rumpus, PANK Magazine, and The Collagist.

Michelle Newby Lancaster is a reviewer for Kirkus Reviews and Foreword Reviews, writer, blogger at TexasBookLover.com, and a moderator for the Texas Book Festival. Her reviews appear in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, Concho River Review, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, The Rumpus, PANK Magazine, and The Collagist.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

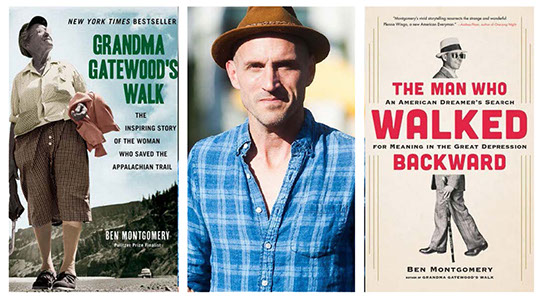

Ben Montgomery is author of the New York Times–bestselling Grandma Gatewood's Walk, winner of a 2014 Outdoor Book Award; The Leper Spy; and The Man Who Walked Backward, coming in fall 2018 from Little, Brown. He spent most of his twenty-year newspaper career as an enterprise reporter for the Tampa Bay Times. He founded the narrative journalism website Gangrey.com and helped launch the Auburn Chautauqua, a Southern writers collective.

In 2010, he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in local reporting and won the Dart Award and Casey Medal for a series called “For Their Own Good,” about abuse at Florida’s oldest reform school.

Montgomery grew up in Oklahoma and studied journalism at Arkansas Tech University, where he played defensive back for the football team, the Wonder Boys. He worked for the Courier in Russellville, Ark., the Standard-Times in San Angelo, Texas, the Times Herald-Record in New York's Hudson River Valley, and the Tampa Tribune before joining the Times in 2006. He lives in Tampa.

Ben Montgomery’s new book of narrative nonfiction, The Man Who Walked Backward: An American Dreamer’s Search for Meaning in the Great Depression, lands on shelves September 18. Montgomery spoke with Lone Star Literary Life about how an interest in agriculture became a career in journalism, the sources of inspiration, amazing women, the Chautauqua tradition, and the swagger of Texas.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: You were born in Oklahoma, Ben. How would you describe your formative years?

BEN MONTGOMERY: My dad was a Southern Baptist preacher and long-haul trucker, which is to say he was something of a stranger to me, a void. My mother ran a day-care center and cleaned the church and tried hard to give me and my brothers what we needed. I spent summers on my grandparents’ farm in Slick, Oklahoma, which wasn’t much more than a wide spot on Highway 16, between Bristow and Beggs. When I wasn't hunting armadillos or arrowheads I’d sit on my granny’s back-porch swing and look out on the wheat field and listen to her tell stories about growing up in Oklahoma. She convinced me I was her favorite grandchild. My brothers never knew. They became rodeo cowboys. I wanted that, too, for a long while, and I went off to college in Arkansas to learn the agriculture business so I could come back to the Plains and live off the land. But her stories planted something inside me I could not escape.

You studied journalism in college and worked at several newspapers, including the San Angelo Standard-Times in Texas, before ending up at the Tampa Bay Times, where you’ve spent most of a twenty-year newspaper career. In 2010 you were nominated for a Pulitzer. What drew you to journalism?

My high-school girlfriend stayed home when I went off to college. I was only four hours east on Interstate 40, but I missed her something bad. And being Southern Baptists, we’d both made promises to God and the youth pastor at church that we would not fornicate before marriage. Her promise was stronger than mine. Alas, I asked her to marry me halfway through my first academic year, and she said yes ... on one condition. She did not want to be a farmer’s wife. I needed a new path. I stumbled into a feature-writing class, and I liked it. I changed my major from ag business to journalism, which might put me in rare company. I’m still in love with words.

You’ve successfully managed to be an author and a journalist. Your latest book, The Man Who Walked Backward, officially launches September 18. Can you tell us about the book and what inspired you to write it?

My first two books were about amazing women, and they felt like noble stories that might pay homage to my mother and granny and a hundred other women who helped raise me. But I didn’t want to be typecast. While researching my first book, I was reading about wild pedestrian stunts and I stumbled onto a few lines about Plennie L. Wingo, a Texan who held the record for the longest backward walk. I gave him a line in my book and could not forget him. Two years passed, then three, and four, and I found myself still thinking about this ridiculous feat. Sometimes, while walking alone, I’d turn around and walk backward and wonder what it would be like to do that for 8,000 miles.

When I realized I could not forget this man, I started doing a little research on the side and a lot of interests clicked into place. I’ve always loved West Texas. I've always been interested in the Great Depression, and oddballs, and quests. Plennie Wingo gave me all that.

The Man Who Walked Backward is your third book. Can you tell us about your two other books, The Leper Spy and Grandma Gatewood’s Walk?

Grandma Gatewood’s Walk is the story of Emma Gatewood, the first woman to ever solo thru-hike the Appalachian Trail, from Georgia to Maine. She walked it in 1955, at age 67. Then did it again. Then again. She was never really widely acknowledged in her day, but the New York Times just recently gave her the proper obituary treatment in the paper's new series, “Overlooked.” That’s pretty cool.

The Leper Spy tells the story of Josefina Guerrero, an unsung hero of WWII. She had Hansen’s Disease — back then called leprosy — a situation that enabled her to penetrate Japanese lines in her homeland, the Philippines. She stole state secrets, mapped enemy gun emplacements, and went on a harrowing journey to warn U.S. soldiers of a massive trap. She saved hundreds of live and was soon forgotten. Her obituary in the Washington Post failed to mention her heroics, or that she’s won the Medal of Freedom. She died in anonymity.

You are one of the co-founders of the Auburn Chautauqua. How did that come about, and how would you describe that group?

I was eating boiled crawfish and crab on my back porch in Tampa with my two best friends — Michael Kruse, now a senior writer for Politico, and Thomas Lake, a senior writer for CNN — and we got to talking about the shortcomings of journalism conferences, which at times feel rushed and impersonal. (It should be noted that the three of us are such nerds that we once took a twelve-hour road trip to eat barbecue with Rick Bragg, who was teaching in Tuscaloosa.) We decided we had enough youthful audacity to do it better. So, we invited a big bunch of writers to get together at Tom’s family's homestead in Ludowici, Georgia. The first was about ten years ago. We do it every October with different writers. The best in the country show up. It’s a magical, incredible weekend. We spend the days challenging each other and critiquing stories, and the evenings we spend playing music and drinking. It sounds lame, but everyone who has been has become family.

You have managed to master newspapering and book authorship simultaneously. Can you tell us what your creative process is like and how you manage to be both journalist and author?

Writing is not hard like roofing a house, or hauling hay, or working in a Tyson chicken freezer. I’ve done that work and I do not mean to draw any comparison. It’s a different kind of hard. Doing both — working eight to six at the paper, then coming home and switching gears and working on the book for four or five or six more hours, was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. Made me feel at times like I was coming apart. It was hell on me mentally and physically, and even worse on my family. I hated it so much that I did it again. And again.

Regarding creative process, all three of my books have gone pretty much like this: I spend about eight months on reporting, interviewing, and research, and I try to leave myself ninety days to write 70,000 words. I aim for a thousand words a day, with the idea that some days I'll have 500 good words and some days 1,500. A lot of friends tell me that’s too fast, but it’s my method, and it has worked for me. I’m sort of scared of getting bored with my subject matter.

What advice would you have for aspiring authors or journalists?

Read the best.

What do you, as from someone who has lived in Texas and written about Texas, find to be most memorable about the state?

There’s a swagger to Texans, a bravado, that the rest of us secretly envy. We will never, ever say this, and we will make fun of it as often as possible, but we long for that Lone Star confidence. It gives rise to folks who are wonderful and some who are terrible, but they're always interesting.

Are you working on a new project or book that you can tell us about?

I am. And I wish I could, but I’m so scared someone will catch on and beat me to it. I’ve just started on the proposal. I have no hesitation when I say I’m more excited about this story than anything I’ve ever worked on.

What books are currently on your nightstand?

I’m halfway through A River Runs Through It and Other Stories by Norman Maclean, which I started as soon as I arrived in Montana, where I’m teaching at university this fall. I’ve shamefully made it forty years without ever having read it, but it’s among the very best writing I’ve ever set eyes on. Others: The Immortal Irishman by Timothy Egan. And a biography of General Bennett H. Young by Oscar A. Kinchen and Edith D. Pope and Her Nashville Friends by John A. Simpson (both research for a possible book).

* * * * *

Praise for Ben Montgomery’s works

“Ben Montgomery is a joy and a wonder, a writer I would happily follow halfway around the world — backward. In fact, I just did, in the compelling company of Plennie L. Wingo, the retrograde ambulator of Abilene, Texas. What a book!” ―David Von Drehl, author of Triangle: The Fire That Changed America and Rise to Greatness: Abraham Lincoln and America's Most Perilous Year

“From Rip Van Winkle to Forrest Gump, Americans have fallen in love with quirky individualists who find their true worth by lighting out into the territory. They were fictional. Plennie Wingo, the man who decided to walk across the globe backward, was real. Wingo turned his back on the Great Depression, an adventure brought to life by the vivid narration of Ben Montgomery, a writer so talented I could read him walking backward.” ―Roy Peter Clark, author of Writing Tools

“In The Man Who Walked Backward, Ben Montgomery lovingly assembles a mosaic of the United States and the world between the wars, told through the life of a small-town Texan who refused to accept his miserable lot during the Depression. Montgomery's vivid storytelling resurrects the strange and wonderful Plennie Wingo, a new American Everyman.” ―Andrea Pitzer, author of One Long Night

“Go, Granny, Go! . . . This astonishing tale will send you looking for your hiking boots. A wonderful story, wonderfully told.” —Charles McNair, books editor at Paste Magazine and author of Pickett’s Charge

“Grandma Gatewood’s Walk is a brilliant look at an America — both good and bad — that has slipped away, seen through the eyes and feet of one of America’s most unlikely heroines. Gatewood’s story suggests anything is possible; no matter your age, gender, or quality of your walking shoes.” —Stephen Rodrick, author of The Magical Stranger

“Grandma Gatewood’s Walk is sure to fuel not only the dreams of would-be hikers, but debates on the limits of endurance, the power of determination, and the nature of myth.” —Earl Swift, author of The Big Roads

“A quiet delight of a book.” —Kirkus Reviews