Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Michelle Newby Lancaster is a reviewer for Kirkus Reviews and Foreword Reviews, writer, blogger at TexasBookLover.com, and a moderator for the Texas Book Festival. Her reviews appear in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, Concho River Review, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, The Rumpus, PANK Magazine, and The Collagist.

Michelle Newby Lancaster is a reviewer for Kirkus Reviews and Foreword Reviews, writer, blogger at TexasBookLover.com, and a moderator for the Texas Book Festival. Her reviews appear in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, Concho River Review, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, The Rumpus, PANK Magazine, and The Collagist.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Randy Kennedy was born in San Antonio, Texas, and raised in Plains, a small farming town in the Texas Panhandle, where his father worked as a telephone lineman and his mother as a teachers’ aide.

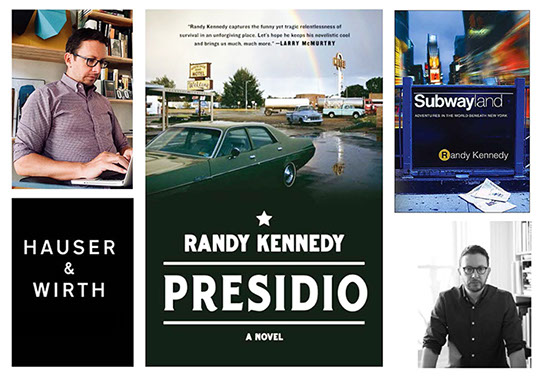

He was educated at the University of Texas at Austin. He moved to New York City in 1991 and worked for twenty-five years as a staff member and writer for the New York Times, first as a city reporter and for many years covering the art world. A collection of his city columns, Subwayland: Adventures in the World Beneath New York, was published in 2004.

For the New York Times and the New York Times Magazine he has written about many of the most prominent artists of the last 50 years, including John Chamberlain, Claes Oldenburg, Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci, Nan Goldin, Paul McCarthy and Isa Genzken. He is currently director of special projects for the international art gallery Hauser & Wirth. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Janet Krone Kennedy, a clinical psychologist, and their two children.

8.26.2018 Randy Kennedy on his debut novel, Presidio, reporting for the NYT, and visual art’s resistance to being written about

Randy Kennedy grew up in Plains, Texas on the Llano Estacado and entered the journalism program at UT Austin where he was a stringer for the New York Times. Upon graduation, Kennedy moved to New York City where he was a clerk at the Times before being promoted to reporter two years later. He wrote for the Times for twenty-five years, first as a city reporter and then covering the art world, before leaving to manage special projects for the international art gallery of Hauser & Wirth. A collection of his Times metro columns, Subwayland: Adventures in the World beneath New York, was published by St. Martin’s Griffin in 2004. His debut novel, Presidio, comes out this month from Touchstone Books.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: How did growing up in Plains, Texas, shape you and impact your writing?

RANDY KENNEDY: I was a bookish kid from the start and not at all built for football, the state religion, so a small, mostly uneventful town gave me long, uninterrupted stretches of reading time. By the age of fourteen or so, I knew I wanted to be a writer. Like many people longing to escape a rural existence, I built up a huge reserve of resentment and grievances, which made for awful, melodramatic writing when I was young. But at least it propelled the writing — and gave me something to atone for later when I wrote a book about West Texas.

You moved to NYC from Austin and wrote for the New York Times for twenty-five years. What or who inspired you to become a journalist?

I fell into journalism in college, at the University of Texas, because I could write pretty well and pretty quickly, and I also had as a role model a cousin, Bob Horton, from Lubbock, who’d had an illustrious career in journalism with the Associated Press and U.S. News and World Report. I thought I’d probably end up making a living as a writer in academia, not journalism. But a daily newspaper, even one run by students, was a thrilling place to be, and I loved it immediately. I started stringing for the New York Times while in college and managed to get a few news pieces into the pages. So, when I graduated in 1991, a Texas friend and I pointed his Honda north toward New York, and I lucked into a job at a Manhattan trade magazine. Nine months later the Times hired me as a clerk and promoted me to reporter within a couple of years.

For the you were a city reporter and also covered the art world for many years. What was it like to move from the Texas Panhandle to the country’s largest metropolis and report on NYC? Were you thrilled and excited or terrified or both? Perhaps neither?

I had Austin as a way station between Plains, Texas (pop. 1400) and New York City. But New York was still overwhelming and sometimes, especially in the early ’90s when crime was so bad and I was sent into crack-war territory with just a notebook in hand, indeed terrifying. For years, I experienced epic mood swings between loving New York with all my soul and wanting to wake up one morning, rent a car, and drive away for good. The pendulum’s arcs are less dramatic now, but every time I look down from a window to see New York City spread out below me during approach, I’m still overcome with joy and wonder that I get to live here. (I have to watch myself, in fact, not to fall into the mindset John Updike once described so astutely: “The true New Yorker secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding.”)

What can you tell us about your passion for art, and abstract and modern sculpture in particular?

My early education didn’t include a lot of art history; I knew virtually nothing about the 20th century. But then in college, I happened into the Menil and the Museum of Fine Art in Houston (I saw my first Rauschenberg there, which blew my doors thoroughly off the hinges). I started reading art history and theory toward the end of college and then, after moving to New York, I saw as much art as time would allow. My tastes tend toward the weird and the dark, anything that actively resists attempts to render in words what it does to the eye and the mind. It might be this difference between writing and visual art — the ineffable quality of much truly great art —that draws me to art. And for the Times I had the chance to spend time with some of best artists of the last half century: John Chamberlain, Isa Genzken, Claes Oldenburg, Bruce Nauman, Nan Goldin, Ida Applebroog, Carl Andre, Robert Irwin, Chris Burden, and Paul McCarthy, just to name a few.

You are currently the director of special projects for Hauser & Wirth, an international art gallery. What does that entail, and why did you decide to move from the NYT to work with art and artists full-time?

I decided, after twenty-five years in daily journalism, that I wanted to try to be a writer and a thinker about art (and other things) outside the prism of the news cycle, which had come to feel repetitive and less and less interesting. I’d never considered working for an art gallery, but Hauser & Wirth, a gallery I respected highly, came to me with ideas for publications and art-historical projects and it immediately made sense to use what I knew about writing, editing, and art to work on projects more deeply connected with artists.

Tell us a little about your debut novel, Presidio. What moved you to write a novel?

I’ve written fiction, and wanted to publish novels, since I was a teenager. I guess I’m a late bloomer! I’d had the idea of the character of a car thief, a modern embodiment of an Old West horse thief, for years, and he wandered in and out of a series of short stories I wrote that often included a younger brother, a good son to the prodigal. I had these in a file I called “Brother Stories” and eventually, as the stories grew and morphed, I came to see that they made more sense woven together as a novel.

What inspired the character of Troy Falconer? What led you to explore a personality who can no longer get along in conventional society? What is it about Texas and the American West that made it the perfect setting for such a person and his story?

Troy is, in some ways, inspired by friends of my father’s, men I knew growing up who were not criminals of any serious nature but always seemed a little flashy and dangerous, drinkers, what you’d call rounders. My dad was a telephone lineman, the son of a struggling dryland cotton farmer, and he worked hard his whole life. He never had the time or inclination to be a wild man, but I think he was drawn to a few who were. At some point in my writing the character, he began to get stranger and more disaffected, to become an almost radical outsider, someone who’d not only left law-abiding society but who wanted to leave society altogether, like a monk, to renounce possessions and everything else about a conventional life. I’m not quite sure why this happened. But I think it did have something to do with realizing myself, somewhere in my thirties, that the United States I was born into — and this was before the digital revolution got fully underway — functioned primarily to train me to be a more efficient consumer and a more efficient worker, in that order. I tried to imagine someone who wanted out, who goes looking for a way of life with more meaning, even at the risk of failing miserably in the attempt.

The reviews of Presidio are astonishing and include favorable comparisons with Cormac McCarthy and high praise from James Lee Burke, Larry McMurtry, and Annie Proulx. McMurtry is famously hard to impress; The Shipping News is sublime: and Burke is my favorite living writer. Where were you when you received the first endorsement and what did you do immediately afterward? How does this critical acclaim from practicing masters affect your work?

I remember being in the subway, looking at my phone, when my editor, Trish Todd, sent me the words that Annie Proulx had written about the book. I’m a huge fan of Proulx’s writing, especially her short stories about the West. I was so stunned and happy that I got a little teary, I’ll admit. It meant so much to me that she had even read it. And for McMurtry to take the time, I frankly still find hard to believe. If they were the only two people who ended up reading the book, I think I could die happy. McMurtry is a god where I grew up, of course, and anybody writing about Texas has no choice but to measure their work against his. As the marvelous Southern novelist Barry Hannah once wrote about his own god, Faulkner: “Salute him or go away. You can’t walk through a statue.”

What can you tell us about your next project?

I’m working on a novel about art, specifically about the boundary between rationality and delirium in the making of art. It will be set in the early 1960s in a mental hospital in the Sacramento Valley of California, where the self-taught genius Martin Ramirez was a patient for most of his adult life and made his drawings, whose importance seems to be recognized more fully in the art world with each passing year.

What books are on your own nightstand?

For the decade when I was writing the book, I tried very hard to stay away from contemporary fiction, or even twentieth-century fiction, because I didn’t want someone else’s voice getting into my head. Now, I’m trying desperately to catch up on what I’d been dying to read for so long. I’m reading Rachel Kushner’s The Mars Room, which is powerfully done. I just finished rereading Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays, so bleak but so beautiful. I’m also about halfway through Elizabeth Hardwick’s collected essays and just started Perfect Wave, the newest collection of essays by the brilliant and always hilarious art-world faith healer (and Texan!) Dave Hickey.

* * * * *

Praise for Randy Kennedy’s PRESIDIO

“Here is a rich and rare book. Reader, if you like poor Texas boys gone bad (or not bad enough), landscapes so accurate in detail you feel you grew up there, coldly logical Mennonite girls with outcast Manitoban-Mexican papas, magnetic details about old cars, the finer points of an automobile-thieving, and a magisterial use of italics you will want to read this novel through twice in a row as I did. It is a hard picture of the choices offered to poor Texas youths in the 1960s and ’70s. You might say it shakes out as a weird combination of Canterbury Tales, “Breaking Bad” and À la recherche du temps perdu with a dash of Confederacy of Dunces, but it is brilliantly original. You will laugh, you will cry and you will read it again straight through to enjoy the fine points of marvelous writing. There is nothing out there like Presidio.” —Annie Proulx, author of Barkskins

“Presidio is set in what I think of as Max Crawford Country — the bleak dreamscape around the edges of the Caprock, where life is, to say the least — gritty. Randy Kennedy captures the funny yet tragic relentlessness of survival in an unforgiving place. Let’s hope he keeps his novelistic cool and brings us much, much more.” —Larry McMurtry\

“Randy Kennedy writes wonderful prose. He combines the detail and eye of a journalist with the lyricism of a poet. If you want to read about the real deal down in Texas, he’s your man.” —James Lee Burke, author of Robicheaux

“Randy Kennedy’s Mexican-American frontier of the 1970s occupies the same dustblown landscape painted by Cormac McCarthy. Car thieves and drug dealers tumble together with Mennonites and luncheonette waitresses — all of them lightened by empty pockets, small dreams, and minimal futures. From these elements Kennedy assembles a gorgeously written narrative of outrunning violence and despair.” —Carol Anshaw, author of Carry the One

“A fabulous novel, executed in rare and exquisite language, about two brothers and the tough little girl (one of the most engaging fictional heroines in recent memory), they accidentally encounter on a hapless journey across Texas to recover some stolen money. Kennedy is truly the literary heir to Cormac McCarthy in his depiction of the vivid characters and sparsely beautiful landscape of the American West.” —Dinitia Smith, author of The Honeymoon

“An absolute marvel of a novel. Like a nesting doll, it continually uncovers stories within stories, each revealing the depth and humanity of its fascinating cast of characters. Kennedy has given us a wonderfully compelling portrait of the American West in the second half of the twentieth century, full of danger, humor, and surprises.” —Ian Stansel, author of The Last Cowboys of San Geronimo

“Two estranged brothers and an unexpected passenger embark on a road trip through Texas to recover stolen money in this strong debut… Kennedy has a fertile imagination he lets drift into many beguiling detours, and the writing sparkles throughout.”

—Kirkus, starred review

“In this stellar debut.... Kennedy soberly etches a Texas landscape of violence and despair as vividly as anything by Larry McMurtry.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Kennedy employs a conversational and reflective tone as he skillfully explores the nature of guilt, identity, and grief in his assured debut. This deceptively polished confessional imbues the three-dimensional characters with humor, cynicism, and considerable pathos in artful contrast to the moonlike landscape of West Texas... For fans of Larry McMurtry and Philipp Meyer.”

—Booklist

“Kennedy creates a reality that blows desert dust into the eyes and cheap motel musk into the nostrils, successfully capturing the intertwining lives of sad sacks who are painfully and at times comically doomed. Those who enjoy classic Western ‘drifter dramas" will be sinfully satisfied.” —Library Journal

* * * * *