Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

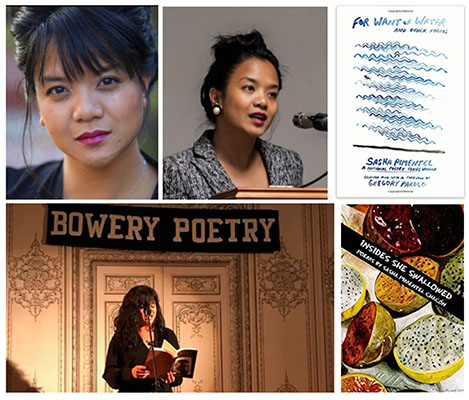

Born in Manila, Philippines and raised in the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, Sasha Pimentel is the author of For Want of Water: and other poems (Beacon Press, 2017), selected by Gregory Pardlo as a winner of the 2016 National Poetry Series. For Want of Water is also winner of the 2018 Helen C. Smith Award and was longlisted for the 2018 PEN/Open Book Award.

Her poems and essays have recently appeared in The New York Times Sunday Magazine, PBS News Hour, The American Poetry Review, and poets.org. She’s also the author of Insides She Swallowed (West End Press, 2010), winner of the 2011 American Book Award. She’s an Associate Professor of poetry and creative nonfiction in a bilingual (Spanish-English) MFA Program to students from across the Americas at the University of Texas at El Paso. In winter 2018–19, she will be the Picador Guest Professor for Literature at Leipzig University in Germany.

4.8.2018 Citizen of the world Sasha Pimentel on the power and the “how” of poetry

At last night’s Texas Institute of Letters induction ceremony in San Antonio, author and teacher Sasha Pimentel was among those honored. A poet of boldness and vibrant imagery, she also took home TIL’s annual prize for the best collection of poems, For Want of Water and Other Poems. We reached out to her via email for today’s interview, and are grateful for her time during a busy week and a busy National Poetry Month.

Where did you grow up, Sasha, and how do you think that experienced influenced your writing?

I was born in Manila, Philippines, which is still the geography to which I attach the word “home” when I think of the word at its most principal, aching level. My parents, brother and I then immigrated to Saudi Arabia and the United States (back and forth a little), so I can also say I grew up in Riyadh, or Jersey City and Stamford, as much as Dhahran and Atlanta, but Manila too, since every number of years we could save up just enough to return from wherever we were to see the family we’d left: how we’d had to recognize the faces we called our own through the foreignness of each other’s new heights, sharpening cheeks or eye sockets — strange lineaments of how we’d aged apart from each other.

That early consciousness of yearning and distance, and how those two become enlaced when you’re an immigrant — it’s essential to who I am, lurks my poems. I think it’s one of the reasons I was drawn to poetry, which by form houses lines that reach or ache across the distance of a page’s whitespace. Though the whitespace is still there, part of the poem always. Poetry has that uneasy wrestling between what reaches (language), and what pushes back (silence) against such reaching. And I recognized that in poetry when I began to seriously study it because it’s something I had already known.

In his “Autobiographical Notes,” James Baldwin says “any writer looking back over even so short a span of time [as one’s life] finds that the things which hurt him and the things which helped him cannot be divorced from each other,” that a writer works from one’s own experience and “out of the disorder of life [recreates] that order which is art.”

Have you always written poetry? How did you come to the form?

I’ve always loved language, singing it, reading it. I developed a love for the English language because I was an interloper in it; the stresses of which I had to listen to, wind my ear up, or mouth deliberately to learn.

I don’t know that I would call what I wrote when I was in high school or college (with my training now), poetry, but the impulse for listening to the sounds of language, and trying to record that listening, was there.

But the first poem I remember reading as personal revelation was Anne Sexton’s “For My Lover, Returning to His Wife.” It was in an anthology Mr. Blackwood had assigned us in high school, and though I was a brown immigrant, had never even nerdily fumbled towards the edges of another awkward teen’s body, somehow I what Sexton was saying. I felt the emotion of it and so knew it, though I knew nothing, empirically, of the matter from which the poem spoke. How could someone do that through words? Reach from such a specific and intimate place to someone who’d never experienced that context, yet still somehow arrive at the reader — bloom inside the reader — so sharply? It penetrated me; I’d felt wrecked by the poem. It was my first real experience with the capacity, and perspicacity, of poetry, and I think I’ve been chasing that “how” as a reader and as a writer ever since.

What was your first big break as a poet?

I think it just happened, when Gregory Pardlo chose my manuscript to win the 2016 National Poetry Series. Through that, the binder-clipped papers became my second book, For Want of Water, with Beacon Press this past October. Beacon is the same press that published Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son and Cornel West’s Race Matters, and Gregory Pardlo launched my poetry into such a humbling space.

Tell us about your latest book, For Want of Water and Other Poems, a semifinalist for the 2018 PEN Open Book Award.

It’s a book about the border, as much as it’s a book that resists what a border is: which is an artificial construction. Our southern “border,” what we call the ragged boundary that countries have wrestled back and forth into territory between México and the United States, is, right now, this magnified object of such U.S. presidential ire and anti-immigrant sentiment.

Though of course such ire is being constructed in the same country which — while expressing such insular nationalism — has always felt free to trespass the sovereignty of other countries and their borders. Has murdered black and brown peoples for economic opportunity and done so having traveled deserts or oceans, as this United States did in the Philippines. Has traveled more oceans, breached countries’ and tribes’ borders to enslave African peoples. Has, within its own borders, displaced or interred its own Japanese American peoples, or who was native here, has sharpened that displacement into the mass murders of indigenous and Black peoples. Has judged, with brutal physical power or smug economic power, always, who they’ve considered enough like “them” for assimilation, and who, judging foreignness upon the motions we move in, the skin we live in, has moved in profound barbarity against the bodies of who was disposable enough to them to enslave and murder. From the early wars against Pequots to Wounded Knee, to the west coast of Africa, Korea, Iraq, Nicaragua, Colombia, México and Cuba, I can go on, the tragedy is that one can go on, like this… — this country’s history, from its origin to is present — is indivisible from its merciless modes of conquest.

For Want of Water is located mostly in the sister cities of El Paso del Norte, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, México, and the recent terrible cartel wars from 2006 to about 2012, in which nearly 100,000 Méxican@s were murdered, when Juárez was often called the most dangerous city in the world. That’s the cold, general description.

Really, it’s about the people I know who hurt, were hurt and who grieved, our silences and mewls, such grief located in our Texas-Chihuahua. And make no mistake: as we swirl dangerously in this ongoing rhetoric of walls, trying to close this border in — though of course I already saw the terrible wall built here — it was brown bodies who fell in the south exactly because bodies in the north were falling to drug and pleasure.

You’ve written and published poetry for more than a decade. What is your creative process like?

Reading and writing. Reading and writing. I’m not trying to be flip or facetious: that really is all I know how to do: read and write and study, read and write. And read some more.

To try to write towards what I admire in what I’ve read.

And to do that over days, which eventually become years.

What brought you to Texas?

I’m very fortunate to be an associate professor in the Department of Creative Writing at the University of Texas at El Paso, where I get to teach poetry and nonfiction in a bilingual MFA program to students who come from across the Americas.

What’s it like to live in El Paso?

The thing that first struck me about El Paso, because I brought to it my body born from the tropics, is how much the body aches for water here. And too the ferocious beauty of this desert, where flowers on cacti bloom from among thorns. The people of El Paso–Juárez, my friends, students, and colleagues, are that fierce and that fervent too.

And over time one develops a relationship with the wind here, which can blow up to forty miles an hour, or which can stop airplanes from descending, can turn rain into falling mud, or land into sandstorm: can shift the landscape here, in just seconds, from one form into another. That’s a very rich thing to witness as an artist and as a scholar, when the land itself is always suggesting newness, possibility.

It’s why I chose the poem “While My Lover Rests” for Lone Star Literary, because the poem is about the wind here, as much as it’s a poem about the rhythms of silence.

What pulls some people to poetry, and some to prose?

I think we write in whichever genres in which can find ourselves capable, and that has to do with what you’re trained for, but also what you’re best tuned for. Some people write both. I just happened to be tuned, as a person, naturally, to silence and music, so that comes out right now as poetry.

What Texas poets do you enjoy reading?

Cyrus Cassells, Naomi Shihab Nye, Sasha West, Rosa Alcalá, Andrea Cote, José Antonio Rodriguez, Benjamin Alire Sáenz, Bobby Byrd, Sheryl Luna… this is not meant to be a comprehensive list by any means; it’s just who I’m reading right now.

What’s it like to be selected for induction into the Texas Institute of Letters?

I can never really reconcile when my work is chosen for anything; I always think they’ve got the wrong person!

But I’m humbled about this, especially because judges Emmy Pérez, Geoff Rips, and Chip Dameron chose For Want of Water to win this year’s 2018 Helen C. Smith Award for Best Book of Poetry, too. I loved getting to go to the ceremony yesterday and learning from the writers around me, learning what I should do in their resounding steps.

Finally, will you share one of your Texas poems with us?

While My Lover Rests

Night divides from my pillow

as a man and a woman, one taking

breath, and the other, moving

to the pattern of his sleep. The soft

palate clicks as measure, and the dead

drip through the window. Here,

the plates of our women’s hips surface

from memory with my nakedness, like a body

and its reflection meeting at the point

of water, and I watch the man alone

in my bed curl, returning. In sleep

we are always aware of the presence

and absence of bodies, and he swims

in delicate ballet to the sheeted

center, knowing the lack of my weight

there. The wind buries herself

against the pane in this lovely, terrible

hour, and all the immigrants I know

of evening are coming to

gather themselves around. Tonight

I am swimming in this

inhalation— exhalation— and the wind,

larger than ever, is wailing, and his

throat relaxes, his uvula aquiver,

and I am listening now and learning

how little my need, in night, to speak.

From Sasha Pimentel, For Want of Water (Beacon Press, 2017)

* * * * *

Praise for Sasha Pimentel's FOR WANT OF WATER

“In this urgent and lyrically astute new compilation, Philippines-born Pimentel, winner of the American Book Award for Insides She Swallowed, writes about the huge divide between El Paso, TX, and murder-slicked, drug war-ravaged Juarez directly across the Rio Grande. . . . Affecting and well wrought; Pimentel is a poet to watch.” —Library Journal

“[Pimentel] excels at crafting a gorgeous language that drapes around the coarseness of the world.” —Publishers Weekly

“Sasha Pimentel threads the complex and intricate geographies of lives across borders: Wyoming, Montparnasse, Saudi Arabia, Ilocos, Manila, but primarily El Paso and Ciudad Juárez in Mexico, where there have been more than forty-eight thousand documented fatalities and more than five thousand disappeared in relation to the drug trade. . . . The crossings Pimentel speaks of are perilous, but I am glad to have her as a guide, because she has the capacity for finding the smallest lights in the incinerated cities, shining through glass or the throats of pipes.” —Luisa A. Igloria, author of Ode to the Heart Smaller Than a Pencil Eraser

“The poetry of Sasha Pimentel is visceral, haunting, searing. This is a poet who sees what most of us would rather not see. Her vision ranges from the thousands of women murdered in Juárez to the single boy dragging the body of his mother, dead of dehydration, across the border into New Mexico. In language of fierce compassion and tenderness, Pimentel humanizes the dehumanized. And oh, how we need such poems.” —Martín Espada, author of Vivas to Those Who Have Failed

“Sasha Pimentel writes evocatively of our irksome obsession—the Mexican border as riddled, tempestuous demarcation between faith and melancholy, expectation and despondency, shadow and glow. El Paso and Ciudad Juárez cling to opposite sides of a hellish boundary—and the poet crafts an existence emboldened by that fracture, trumpeting the triumphs and hazards of a love that defies its ragged edict. No other poet has dared this landscape with such a deft and intrepid touch, conjuring an expansive, revelatory and indispensable read. Nothing—nothing—in these pages has been done before.” —Patricia Smith, author of Incendiary Art

* * * * *