Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

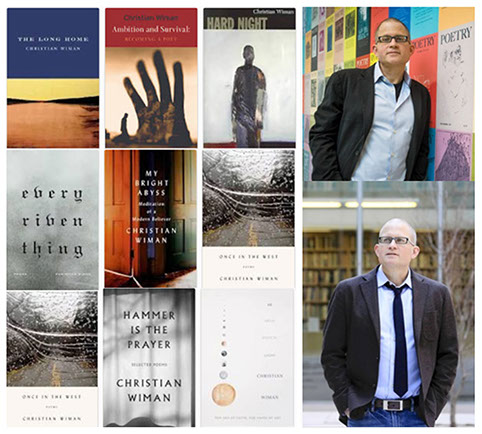

4.1.2018 Poet, essayist, and teacher Christian Wiman on faith, a passion for poetry

It’s a long way from West Texas to New Haven, and few would agree more than widely respected, award-winning poet Christian Wiman. I first met Christian some years back, when he returned to his home state for a reading at Texas Tech University, and found his poetry evocative of the West Texas I knew from my own childhood. It seemed only fitting to ask him, since he’s among the nineteen 2018 inductees to the Texas Institute of Letters in San Antonio next week, to kick off our Poetry Month coverage in Lone Star Literary on Easter Sunday. We corresponded via email for this interview.

Christian, I understand that you grew up in Snyder, in West Texas. How would you describe those days?

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, etc. When my family was intact, we had a rich life there. Things began going haywire when I was fourteen or so, and from that point I just wanted out.

When did writing become a part of your life?

When I was very young. I don’t remember ever reading poetry at home or in school, so I suppose I was imitating the hymns and Bible verses I heard all the time. But I didn’t know there was such a thing as a living poet until I went away to college.

You graduated from Washington and Lee, a private liberal arts college in Virginia. What made you choose that university and what was that experience like for you?

See above. I wanted to get away, and Virginia seemed like another world (as indeed it was). Why that school in particular? In all honesty, it was the only out-of-state school to send me any information in the mail. Being there was a shock — existentially, first of all, because I met many people who did not share the beliefs of the world in which I had been raised; and practically, because I paid for everything myself, which was tough.

What do you consider to be your “first big break” in your writing career?

When I was 24 I was living in a trailer in my grandmother’s back yard in Colorado City [Texas], and I applied, on a whim, for a two-year writing fellowship at Stanford. They only gave four a year, and I got one. It opened up a lot of doors.

Your first book of poetry, The Long Home, was published in 1998. Can you tell us about that book and that experience?

That book actually emerged directly out of the experience of living with (or near) my grandmother and aunt (who shared the house with my grandmother). I had a hard time finding ways of talking to them for extended periods, until one day I began asking about the past. That let loose a flood of feelings, in all of us, and eventually I realized that I had found my first book.

From 2003 to 2013, you were editor of the oldest American magazine of verse, Poetry. How did the appointment come about, and what was that experience like?

I had written a lot of prose for the back pages of the magazine, so I knew the editors well. In 2003 Poetry, which was a relatively poor magazine, received a much-publicized gift of two hundred million dollars. That changed everything, and in all the turmoil, I found myself at the right place at the right time.

I loved many aspects of the job, especially being able to make such a difference in the lives of young poets, but it was very, very demanding, and for the first few years I hardly wrote a word of my own at all.

In 2013 you stepped down from the editorship of Poetry. Will you share with our readers what prompted that decision?

I had been there for ten years, which is long enough for any editor of a literary magazine. You lose your ability to detect what is truly fresh. So I knew that I was going to leave, but I made the move to Yale Divinity School in particular because I wanted some way of uniting my passion for poetry with my faith.

Your most recent book — your tenth — He Held Radical Light: The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art will be published in September. Can you tell our readers about the personal journey that you took you to this book, and a bit about the book itself?

This book tries to answer the question of what it is that we want when we can’t stop wanting. “God” is not quite the answer I come to. The book centers around encounters I have had with well-known writers over the years.

You have been selected for induction into the Texas Institute of Letters, an event that takes place in San Antonio in a few days. What's it like to be recognized as one of Texas leading writers?

It’s a great honor. Years ago I spent half a year at the Dobie Paisano Ranch near Austin and was invited to the TIL banquet, which I wandered around aimlessly and eventually snuck out of alone. It will be nice to be there in a more bracing way!

During National Poetry Month, we like to not only recognize Texas poets, but we also like to share one of their poems that evokes a sense of Texas for the poet. Would you be able to share one of your poems with us?

Sitting Down to Breakfast Alone

Brachest, she called it, gentling grease

over blanching yolks with an expertise

honed from three decades of dawns

at the Longhorn Diner in Loraine,

where even the oldest in the men’s booth

swore as if it were scripture truth

they’d never had a breakfast better,

rapping a glass sharply to get her

attention when it went sorrowing

so far into some simple thing —

the jangly door or a crusted pan,

the wall clock’s black, hitchy hands —

that she would startle, blink, then grin

as if discovering them all again.

Who remembers now when one died

the space that he had occupied

went unfilled for a day, then two, three,

until she unceremoniously

plunked plates down in the wrong places

and stared their wronged faces

back to banter she could hardly follow.

Unmarried, childless, homely, “slow,”

she knew coffee cut with chamomile

kept the grocer Paul’s ulcer cool,

yarrow in gravy eased the islands

of lesions in Larry Borwick’s hands,

and when some nightlong nameless urgency

sent him seeking human company

Brother Tom needed hash browns with cheese.

She knew to nod at the litany of cities

the big-rig long-haulers bragged her past,

to laugh when the hunters asked

if she’d pray for them or for the quail

they went laughing off to kill,

and then — envisioning one

rising so fast it seemed the sun

tugged at it — to do exactly that.

Who remembers where they all sat:

crook-backed builders, drought-faced framers,

VF’ers muttering through their wars,

night-shift roughnecks so caked in black

it seemed they made their way back

every morning from the dead.

Who remembers one word they said?

The Longhorn Diner’s long torn down,

the gin and feedlots gone, the town

itself now nothing but a name

at which some bored boy has taken aim,

every letter light-pierced and partial.

Sister, Aunt Sissy, Bera Thrailkill,

I picture you one dime-bright dawn

grown even brighter now for being gone

bustling amid the formica and chrome

of that small house we both called home

during the spring that was your last.

All stories stop: once more you’re lost

in something I can merely see:

stream spiriting out of black coffee,

the scorched pores of toast, a bowl

of apple butter like edible soil,

bald cloth, knifelight, the lip of a glass,

my plate’s gleaming, teeming emptiness.

From Christian Wiman, Every Riven Thing (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010)

* * * * *

Praise for Christian Wiman's MY BRIGHT ABYSS

“[Christian Wiman’s] poetry and his scholarship have a purifying urgency that is rare in this world. This puts him at the very source of theology, and enables him to say new things in timeless language, so that the reader’s surprise and assent are one and the same.” ―Marilynne Robinson, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Gilead

“Every generation needs someone to write about faith as lucidly as Christian Wiman does in this ‘meditation of a modern believer.’” ―Wall Street Journal

“Like the classic mystics, [Wiman] often resorts to a language of paradox to convey things that ordinary language can’t … Wiman speaks carefully but powerfully . . . The best that can come from contemplation of mortality, perhaps, is a kind of wisdom that can give others strength — not by answering questions, like those best-sellers which claim to tell you what happens after you see the white light, but by asking questions honestly . . . My Bright Abyss is a book that will give light and strength, even to those who find themselves unable to follow its difficult path.” ―Adam Kirsch, The New Yorker

“This is a daring and urgent book . . . More than any other contemporary book I know, My Bright Abyss reveals what it can mean to experience St. Benedict’s admonition to keep death daily before your eyes . . . Wiman is relentless in his probing of how life feels when one is up against death . . . With both honesty and humility, Wiman looks deep into his doubts his suspicion of religious claims and his inadequacy at prayer. He seeks ‘a poetics of belief, a language capacious enough to include a mystery that, ultimately, defeats it, and sufficiently intimate and inclusive to serve not only as individual expression but as communal need. This is a very tall order, and Wiman is a brave writer to take it on . . . Wiman mounts a welcome, insightful and bracing assault on both the complacent pieties of many Christians and the thoughtless bigotry of intellectuals who regard Christian faith as suitable only for idiots or fools . . . This pithy and passionate book is not easy, but it is rewarding. Wiman’s finely honed language can be vivid and engaging . . . He exhibits a poet's concern for precision . . . This is, above all, a book about experience, and about seeking a language that is adequate for both the fiery moments of inspiration and the ‘fireless life’ in which we spend most of our days. It is a testament to the human ability to respond to grace, even at times of great suffering, and to resolve to live and love more fully even as death draws near.” ―Kathleen Norris, New York Times Book Review

“Burnished and beautiful, My Bright Abyss is a sobering look at faith and poetry by a man who believes fiercely in both, but fears he might be looking at them for the last time. Wiman’s memoir is innovative in its willingness to interrogate not only religious belief, but one of its most common surrogates, literature . . . Wiman’s story is chiefly a love affair: of a poet with words, of a husband with his wife and two daughters, of a believer with the holy . . . Here is a poet wrestling with words the way that Jacob wrestled the angel . . . Wiman calls his memoir the “Meditation of a Modern Believer,” and it is that, but more than meditation, it is an apologia and a prayer, an invitation and a fellow traveler for any who suffer and all who believe.” ―Casey N. Cep, The New Republic

“In verse and poetry alike, Christian Wiman possesses and endearing and profound spiritual sensibility . . . My Bright Abyss is built of prose so lyrical and true you want to roll it around in your mouth and then speak it to strangers on the street . . . Wiman refuses easeful conclusions, he celebrates the verse and the two-faced joy at the hub of our lives — Nietzsche’s tragic joy--and in doing so he has written what will be for many a life-changing book.” ―William Giraldi, Virginia Quarterly Review

“Wiman infuses his writing with lyricism and a playfulness with language . . . He augments his own mastery of language with the liberal use of quotations from other poets and writers, spanning an impressive range of literary backgrounds. Wiman’s depth of knowledge as a reader truly undergirds this work, as he invokes everyone from George Herbert to Simone Weil, Dietrich Bonheoffer to Seamus Heaney. As the author struggles to understand God, he also struggles to comprehend the institution of Christianity, seeing in it deep flaws, an inability to fully grasp the depth of the God it proclaims, and what he sees as a childish clinging to legend and myth . . . Poignant and focused . . . Wiman’s grasp of the written word carries this unconventional faith memoir.” ―Kirkus

* * * * *