LAUNCH EVENT: 7-9 p.m. Wednesday, February 13, 2019, Austin Central Library, 710 West Cesar Chavez Street

LAUNCH EVENT: 7-9 p.m. Wednesday, February 13, 2019, Austin Central Library, 710 West Cesar Chavez Street

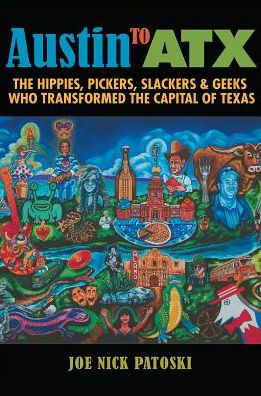

Joe Nick Patoski launches his tenth book, Austin to ATX. Patoski will read from and discuss the book with Austin American-Statesman writer and Austin historian Michael Barnes, and sign copies afterwards. Jon Dee Graham will perform a short set of Austin songs from different eras. Books will be available for purchase at the event through BookPeople. This event will be held in the Central Library’s Special Events Center. Doors open at 6:30 pm.

Lone Star Literary Life: Mr. Patoski, your new book is Austin to ATX: The Hippies, Pickers, Slackers & Geeks Who Transformed the Capital of Texas, a history of the culture and growth of our beloved “blue dot.” Why this book and why now?

Joe Nick Patoski: I’ve wanted to take on this subject for the last ten years. What is it about Austin that makes it different from the rest of Texas? What’s that element that continues to attract people even as the city risks choking on its own success?

LSLL: What sort of magnetism, or as you term the phenomenon, “cosmic accidents,” is at work in Austin that so many iconoclasts ended up in the same place?

JNP: The creatives drive Austin’s culture. The economies of Texas’s other big cities are built on the extraction of natural resources, i.e. oil and gas. Austin’s economy in the past half century has been fueled by the creative mind.

LSLL: During a recent podcast, you said that there are three institutions that built old Austin—the University of Texas, the state capital, and the oldest continuously operating business, Scholz Garten, (which is a second home of a certain cousin of mine). Why these three and how do they work together?

JNP: There is general consensus that the university and state government have been the pillars that the city was built upon. Both provide employment, and the university has been the recognized hub of creativity since its founding. The third institution, Scholz Garten, is less recognized but just as defining. The oldest business in the city is a singing club founded by Germans to make music, drink beer, and dance. That informs the locals’ refined pursuit of pleasure. You come to Austin to have a good time.

LSLL: Gentrification. Can we talk about gentrification? There have been recent moves to attempt to mitigate the effects of gentrification; East Austin comes to mind. Is there any hope?

JNP: There is no easy solution to gentrification. People recognize it’s an issue, but there is no silver bullet here. It’s disappointing that the last ethnic neighborhoods in the city are being erased. That speaks more to how money has come into play in Austin with tech. People who aren’t making a boatload of money are being forced to suburbs and surrounding small towns, including musicians, artists, and other creatives. Pushing out Mexican-Americans and African-Americans whose heritage defined East Austin and forcing creatives to move to cheaper places to work out their ideas is not a good thing.

Austin’s creativity exploded in the '70s mainly because Austin had the cheapest cost of living of the one hundred largest cities in the United States. You could work out your ideas or indulge in whatever floated your boat. Today, artistic types in Austin have to be entrepreneurs or have income from elsewhere to be able to afford to live here.

But as much as this is a recognized challenge to Austin’s future, I’m always reminded by a walk through the Upper West Side of New York—it was all midcentury high-rise apartments, but on a corner I saw a nineteenth-century brownstone. That’s when I realized that once upon a time, all of the Upper West Side was brownstones. It kind of reminds me of the Broken Spoke and how it’s surrounded by condos now.

LSLL: You moved to Austin in 1973 and so have had a front-row seat to much of what Texas Monthly called Austin’s “dramatic transition from small town to global city.” From where did you move and why Austin?

JNP: I moved to Austin with my girlfriend (now wife, Kris Cummings) from Minneapolis. I had been running the record department of the Electric Fetus, a store that just celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. It was a kid-in-a-candy-shop gig. While I was there, I started writing about music. A review I’d submitted over the transom to Creem magazine, about an album of outtakes of Sir Douglas Quintet tracks that Mercury had issued to capitalize on Doug Sahm’s Atlantic album with Bob Dylan, got published. I received a thirty-dollar check and a handwritten letter from Lester Bangs, one of my music writing role models, encouraging me to write more. At the same time, I was reading all these stories in Rolling Stone and Creem magazines about Austin that Chet Flippo was writing, in particular a story he’d written about Doug Sahm playing at Soap Creek Saloon. A scene was developing in Austin. Much as I loved my job at Electric Fetus, Minneapolis wasn’t home—I was reminded when it snowed in early May.

I wanted to go back to Texas. I’d grown up in Fort Worth, but it was hostile ground for a long-hair who thought different. I’d known enough about Austin through numerous visits growing up, and I’d checked out the Armadillo and met Jim Franklin and Eddie Wilson in 1971 when I was working as an underground rock-radio disc jockey on KFAD in Dallas-Fort Worth. On my next visit, my Fort Worth friends Dave Thompson and Don Crowell took me to the Split Rail to see Freda and the Firedogs, the first hippies I’d seen who played hardcore country music to the broadest mix of music fans I’d ever seen.

So, when I came home, it was to this place I’d never lived before. A couple weeks after we arrived, we went to Soap Creek Saloon to see Doug Sahm. It was everything that Chet Flippo had written about—even better. At that point, in a sweaty little roadhouse on the western outskirts of the city, I knew I had found my place.

LSLL: You’ve written for the Texas Observer, the New York Times, National Geographic, and Texas Monthly, among many outlets. You’ve written books about musicians, mountains, and football, and recorded personal histories for the Voice of Civil Rights oral history project sponsored by AARP and the Library of Congress. What common thread connects you to these disparate subjects?

JNP: My curiosity, a good story, and a sense of place are elements that tie together the wide range of subjects I’ve written about. Music came first, but pretty soon I was branching out into culture, travel, and the chase to figure out how places inform people and their actions. Texas, of course, is a constant theme. People outside of Texas seem fascinated by what it is and who we are. I like knowing more about the turf I’m on and Texas remains distinct, independent, and sufficiently provincial and separate from what I call "Generica," to be of interest.

LSLL: My favorite book of yours so far is Texas Mountains (University of Texas Press, 2001); the jacket art stopped me in my tracks in the little shop at Guadalupe National Park so I bought it and read the whole thing next to the pool at Balmorhea. (I considered turning an otherwise perfectly good beagle over to a shelter when she gnawed on that book—she ate a third of the jacket, I think.) You’ve said you’d been working on that book for forty years but didn’t realize it. Please explain. And have you gotten around to climbing North Mount Franklin yet?

JNP: I’d been working on Texas Mountains for forty years because I was eight years old when my father took my sister and me to Big Bend. We’d gone to San Antonio to see the Alamo because I was a Davy Crockett nut, down to my coonskin cap and buckskin outfit. But when I laid my eyes on the Alamo, I was bummed. That’s it? It was so diminutive compared to what I had imagined, crammed into downtown. I think the Ripley’s Believe It Or Not “museum” across the street left a bigger impression. But after spending the night in Marathon we drove to Big Bend National Park and I was dazzled. Real mountains! Sprawling desert! This was the Texas I’d imagined, big enough to swallow up a little kid.

Whenever I’m in Chisos Basin, I always look at the little hill by the visitor center and smile because when I scurried up on my first visit, it felt like a mountain to me. Laurence Parent’s landscape photographs are stunning, but if you pay attention, there are no people in his shots. I filled that in with stories of locals from Hallie Stillwell to Boyd and Johnnie Chambers. Outside of El Paso, the population of the region where the Texas mountains are is less than fifty thousand, but practically everyone has a story to tell, and the art of conversation remains strong and vital out that way. The region is variously described as the Trans-Pecos and the Big Bend. Laurence and I were first to use the conceit “Texas Mountains”—because this is where the mountains are in Texas.

I haven’t climbed North Mount Franklin yet, but I have walked the spine of the Franklins from Stanton Street in inner-city El Paso to Transmountain Road in a single day.

LSLL: You have written extensively and widely about music, as well as hosting the “Texas Music Hour of Power” on KRTS FM Marfa, which I tune in every time I find myself near the Bend. What role has music played in your life? Is there a Texas, or Austin, sound?

JNP: Music is a driving force in my life and has been since I was three, when I had my parents buy me a copy of the Sons of the Pioneers’ “Cool Water.” I loved banjo when I was a kid; my first concert was seeing Homer and Jethro open for Tommy Sands in Fort Worth when I was five. I made my mother take me backstage to meet Homer and Jethro, who were parodists who happened to be great banjo, mandolin, and guitar players. When I was six, I took accordion lessons and learned a song called “The Primo Waltz” before I lost interest. I played violin in second grade and as a young teen tried to learn guitar. I really couldn’t play. I remain the only one in my family now who can’t play, even though I have a button accordion I tool around with.

In junior high, I’d walk a mile to KFJZ to pick up their weekly Top 40 survey, and the disc jockeys would let me watch them work. By high school, I was the guy booking the bands in my fraternity. Then after high school, I had a small record shop; got my third class FCC license to be a broadcaster; and scored that gig at KFAD for $1.60 an hour, minimum wage. The station had an incredible library of rock and jazz, and my job was to play the advertisements on the schedule and play good music, no holds barred. It was one of the best jobs I’ve ever had.

All that led to writing about music, first for the Prospector at the University of Texas at El Paso, my first university. I was tired of guys in the dorm saying, “This is great!” or “That sucks!” I wanted to delve deeper, where the writers were going in these new music magazines like Rolling Stone that I was devouring.

To me, Texas music can mean just about anything, as long as it’s authentic and has soul. In the song “At The Crossroads,” Doug Sahm sang that “you just can’t live in Texas, if you don’t have a lot of soul.” That’s about right. Texas music is at the crossroads: on the western edge of the South; as the gateway to the West; the one state that interfaces with the heart of Mexico and Latin America; and sufficiently isolated from either coast to be provincial and unto itself. Add the cowboy tradition of telling stories around the campfire, and the Mexican-American tradition of the corrido—telling the news in songs, and you’ve got Texas music. The roots of Southern music—where jazz, blues, and country music come from—are Anglo-American and African-American. Only Texas music has the tri-ethnic foundations of Anglo-American, African-American, and Mexican-American—another asset that separates Texas music from all other music.

On the "Texas Music Hour Of Power," I try to play all those different strands, from the beginning of recorded music all the way to the present, to show why our music is better than Iowa’s, California’s, or Tennessee’s.

LSLL: You directed your first film in 2015, a music documentary about Texas singer-songwriter Doug Sahm called Sir Doug & The Genuine Texas Cosmic Groove, which premiered at the South By Southwest Film Festival. With so many Texas singer-songwriters out there, what inspired you to choose Sahm? What was the filming process like for you and is there another Patoski film in our future?

JNP: I chose Doug Sahm because seeing him and getting to know him was a life-changer. No single person could play all the indigenous sounds of Texas—blues, country, western swing, conjunto, Cajun, and rock and roll—authentically like Doug could. He was the beneficiary of direct transmission, a steel guitar and fiddle prodigy as a child who sat on the knee of Hank Williams, country music’s biggest star, who also lived across a cotton field from a genuine Chitlin’ Circuit club where as a teen he watched and learned from T-Bone Walker, the Father of the Modern Electric Blues Guitar, Gatemouth Brown, and other black blues giants. Then he was the gabacho (white boy) who ventured to El West Side of San Antonio to soak up the Mexican sounds and in the process “discovered” Flaco Jimenez.

When I got to Austin in 1973, Michael Murphey, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Willis Alan Ramsey were the big dogs who pulled in the crowds and got played on the radio. But I was drawn instead to this old forty-year-old guy from Nashville named Willie Nelson who was rocking up his sound, and by Doug Sahm, who had returned from several years in San Francisco. Doug was the one guy in Austin who had had hit records with the Sir Douglas Quintet’s “She’s About A Mover” and “Mendocino,” and the fact he came back from San Francisco and moved to Austin, after getting hassled in San Antonio for his long hair, was a signal. Hippies didn’t need to leave Texas for San Francisco anymore, like Janis Joplin and Johnny Winter had done only a few years later. Austin was cool enough. Doug being here made it so. We all know what happened to Willie, but most folks have never heard of Doug. That’s why I did the film.

Film is a whole different kind of storytelling. It’s a very collaborative effort, and sometimes liberties and shortcuts are taken—what I call verisimilitude—to tell a story effectively. With writing, I try to put as much detail on the page. With filmmaking, it’s more like, what does it take to move the story along. That said, being at screenings and hearing people clap and yell at the end is a rewarding rush that I don’t get with writing a book. Film is the best way to reach the largest audience if you have a story to tell. But like I said, it’s extremely collaborative, meaning compromises are constant, and it’s very expensive to do. I can do a book for one-tenth the cost and tell a story pretty much the way I want to tell it, without too many outside voices weighing in.

LSLL: Can you tell us what you’re working on now and what’s next for Joe Nick?

JNP: Right now, I’m finishing pieces I’m doing for Texas Highways magazine on the Laguna Madre and on Los Texmaniacs, and lining up some stories up on Route 66 in the Panhandle and out west of the Guadalupe Mountains National Park. I like having a purpose to my wanderings and these kind of articles do that. I recently contributed to the DVD package of the reissue of the film True Stories that David Byrne did back in the 1980s and wrote an essay for the “Outlaws and Armadillos” exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame that’s up right now.

I’m wearing many hats while promoting Austin to ATX for the next couple or three months while looking for that great big story that I can dive into for a year or two and make a book out of it. Odds are it’ll be set in Texas.

JOE NICK PATOSKI writes about Texas and Texans. A former cab driver and staff writer for Texas Monthly magazine, and one-time reporter at the Austin American-Statesman, he has authored and co-authored biographies of Willie Nelson, Selena, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and the Dallas Cowboys, and collaborated with photographer Laurence Parent on books about the Texas Mountains, the Texas Coast, and Big Bend National Park. He wrote essays for the 2015 book Homegrown: Austin Music Posters, 1968-1982 and Conjunto by John Dyer with Juan Tejeda. He has covered conservation in the book Generations on the Land: A Conservation Legacy and the state religion of Texas in the book Texas High School Football: More Than the Game.

Patoski’s byline has appeared in the New York Times, National Geographic, the Texas Observer, Oxford American, TimeOut New York, Garden and Gun, and No Depression magazine, for whom he was a contributing editor. He recorded the oral histories of B.B. King, Clarence Fountain of the Blind Boys of Alabama, Memphis musician and producer Jim Dickinson, Tejano superstar Little Joe Hernandez, and fifteen other subjects for the Voice of Civil Rights oral history project sponsored by AARP and the Library of Congress, some of which appeared in the book My Soul Looks Back in Wonder by Juan Williams.

In 2015, Patoski directed his first film, the music documentary Sir Doug & The Genuine Texas Cosmic Groove, which premiered at the South By Southwest Film Festival.

He hosts the "Texas Music Hour of Power," broadcast on KRTS FM Marfa www.marfapublicradio.org Saturdays 7 – 9 pm central, and lives near the Texas Hill Country village of Wimberley where he swims and paddles in the Blanco River.