LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Where did you grow up, Michael, and how would you describe those days?

MICHAEL HURD: I was born in Texarkana, Texas side (!). Despite the segregation in the 1950s, I look back at that as the best time in my life. We had a wonderful family centered around my maternal grandmother — my “Big Momma!” There was always somebody to give you a hug, or tell you to get me a switch!, or offer a lap to sit in, or walk with you to church every Sunday. My grandmother, Ellen Baxter, my uncles and aunts, cousins were the best people I’ve ever known. Solid human beings who loved family, loved kids, and were well-respected in the community. It was such a loving and supportive environment. We moved to Houston when I was ten, and I was mad at my parents for the longest time because I didn’t understand why we had to move, why we had to leave that.

How old were you when you first played football, and what position did you play?

I didn’t participate in team sports at school, but played sandlot games — touch football, sometimes tackle, basketball, Little League baseball. I started playing those sports early on with my friends, and we’d have neighborhood teams that played against neighborhood rivals. I didn’t have a lot of confidence in my athletic ability until I went into the Air Force and found out I could compete, especially in basketball. I was a late bloomer athletically and had an opportunity to walk on in basketball at UT when I got out of the Air Force. Abe Lemons was the coach. Couldn’t have been nicer — “Just show me you can play.” I did not. Coming off an Achilles injury didn’t help. I didn’t make the team, but I got a pretty good column out of the experience when I started writing for the Daily Texan. Talked with Abe several years after that and he told me he’d read and really liked the column, so much so that he carried it around with him for quite a while.

In high school, you followed football at segregated schools in Houston in the 1960s. How did that experience inform Thursday Night Lights?

It formed the background for the book. I attended Worthing High School, which was segregated, in southeast Houston, Sunnyside. I didn’t play on the football team but was an avid fan. Our games were on Wednesday or Thursday nights, and I rarely missed one. I write in the book that I felt like I had been writing that story since adolescence because watching the all-black teams in Houston was my high school football experience, going to those games at Jeppesen Stadium in Third Ward — the black culture hub — and being familiar with the coaches and players, some of who were my classmates and friends. The book’s story evolves from that time for me.

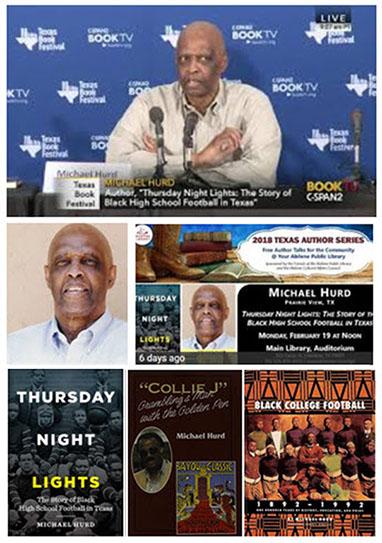

For our readers not familiar with Thursday Night Lights, will you tell them about your book?

The book is meant to both remember and introduce the Prairie View Interscholastic League and the all-black teams that competed under that banner for fifty years (1920 to 1970) as the mirror organization to the University Interscholastic League in the segregationist era.

The UIL got its start at the University of Texas in 1910 and specifically stated its membership was open only to “any public white school.” The PVIL started in 1920 at Prairie View A&M as the governing body for black high school athletic, academic, and band competitions statewide, which the UIL was doing for white schools. Black schools in Texas that shared public school stadiums with white schools held their games primarily on Wednesday and Thursday nights, white schools on Friday and Saturday nights. The book traces the PVIL’s football lineage — why and how it got started, how it came to an end with integration; and I profile some of the players, coaches, and teams who participated in the league. The PVIL teams got very little, if any, mainstream media coverage, but it produced a ton of talent with players like “Mean” Joe Greene, Ken Houston, “Night Train” Lane, Bubba Smith, Jerry LeVias, Otis Taylor, and so many others.

I've read in interviews your comments about what it was like to be a young black man during the change from segregation to integration. What stands out in your mind from those days?

I graduated from Worthing in the spring of 1967, and that fall was the first high school season for integration, black schools competing against white schools, some of which had integrated teams for the first time. I went back for homecoming that fall and it was so different — it was not at Jeppesen Stadium in Third Ward, but in southwest Houston and the game was against a white school. It didn’t have the same feeling I had from all the previous years of going to the games. I left at halftime. But that was such a microcosm of the societal changes that were going on and I knew a lot of things, so much more than just football games, were about to be different.

You graduated high school in 1967 and then, in 1970 you went to Vietnam for a year and served in the Air Force until 1976. How did that change your life?

I was a good student in high school, and my journalism teacher, Bruce Webb, offered to help get me into the University of Houston, and I applied to some other schools, but deep down I wasn’t ready for college. I wanted a break from studying and to get away from home and be on my own, see the world. Start growing up.

It was one of the best decisions of my life. I had never interacted closely with non-black people, had no friends that weren’t black, but immediately knew I had done the right thing. For the first time, I met and became friends with people from all around the country, the world! One of my first roommates was a guy from Topeka, Kansas. He’d never met a black person! So, after lights out, we’d sit in the dark getting to know each other, getting to know how, despite our races, how much we were alike. That’s the kind of thing that really impressed me. I enjoyed meeting and getting to know people from different backgrounds and ethnicities. I’d never felt inferior because I was black and my experiences in the Air Force confirmed that I had no reason to feel that way. I’ve always enjoyed meeting people and that carried over to my journalism career, meeting people and telling their stories.

After the military, you attended the University of Texas, though both of your parents had attended historically black colleges. What made you choose UT?

My mom, Emily Hurd, went to Bishop College in Marshall as a 14-year-old piano prodigy. My dad, James Hurd, briefly attended Virginia State University, and I had relatives who went to Texas Southern and Fisk.

Out of high school, I wasn't too excited about it, but I had one foot in the door at Texas Southern. However, Uncle Sam, during the Vietnam era, had the other foot and I ended up in the Air Force. After eight and half years of service, I was ready to get back in school and wanted to challenge myself — academically and socially — and UT seemed the right place for that, despite its negative history with African Americans. But I didn’t really care about that stuff. I was 27, somewhat worldly. I just wanted to go to a good school, and UT was the best. My brother was already there, studying music, so I thought it would be good for me. And it was! Like the Air Force, I met and learned a lot about people, had good professors, made some lifelong friends and got into a great journalism program. One of my professors, Red Gibson, recommended me for my first job, in my junior year. A few years later, I went back and asked him why he’d done that for such a greenhorn: “I just thought you were ready.”

After attending college for a few years you took a position as a sports reporter for the Houston Post. Later on, in your journalism career, you were part of the founding team of USA Today, writing sports news for them as well. What sports journalists and sports authors, over the years, have you enjoyed reading?

I grew up religiously reading Houston Post columnist Mickey Herskowitz. That guided me towards a career in journalism. But I read Jim Murray, Dan Jenkins, Bud Shrake, and going way back, Ring Lardner. I have many friends who are phenomenal reporters and writers, I hesitate to mention names, because I don’t want to slight anybody, but Jim Dent’s work on high school football — The Kids Got It Right, and college football — The Junction Boys — was really inspirational for me in regard to researching and writing Thursday Night Lights. Oh, and the late Jack Gallagher, at the Post. I was there for a couple of years with Jack and really admired his work ethic and writing. When I left the Post, he told me, “You know, when you first got here, I didn’t think much of you. But now, hell, you’re as good as the rest of us.”

When you left college in 1979 to go to work at the Houston Post, you didn’t finish your degree, but you went back to UT in 1997 to complete it. Why was that important?

I wanted that credential and all the validation it brings about hard work and intellect. But also, like so many folks, because of my mom. I’m from a family of teachers, so lots of skins on the wall in the Hurd, Baxter, and Dodd families in East Texas. All four of my grandmother’s kids got college degrees. My mom taught second grade. So we always had books around and knew the importance of getting an education. She was my biggest fan but passed before I went back to complete my degree at UT. I promised her when I left UT early to start my sports-writing career, I’d go back at some point and finish. Ironically, when I initially expressed doubts to her about going to UT and being skeptical about my ability to make it, she thought that was the funniest thing she’d ever heard. “You’ll make it.” She never doubted my ability to do anything. So getting my degree was very much a nod to her.

One final, important question for readers in these times. As a lifelong journalist who moved to academia and book publishing in recent years, what advice do you have for current working journalists when facing accusations of “fake news”?

I think working journalists know what that’s all about, an attempt to divert from the truth resulting from the good work, good reporting, that’s being done. No reputable reporter buys into that claim. Ignore that kind of noise and keep working, being professional about what you do and how you go about reporting and writing.

Michael Hurd is the director of Prairie View A&M University’s Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture, which documents the history of African American Texans. He has worked as a sports writer for the Houston Post, the Austin American-Statesman, USA Today, and Yahoo Sports. Hurd’s previous books include Black College Football, 1892–1992: One Hundred Years of History, Education, and Pride. For more than a decade, he served as a member of the National Football Foundation’s Honors Court for Divisional Players, the group that chooses small college players for the College Football Hall of Fame, and he currently serves on the selection committee for the Black College Football Hall of Fame.