Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

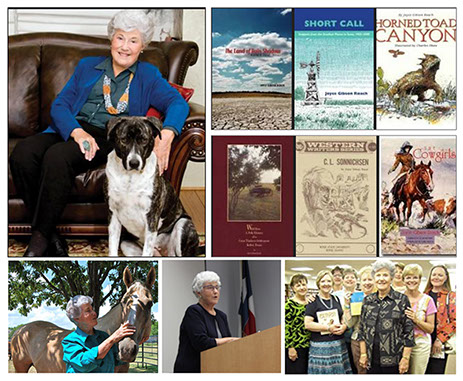

Joyce Gibson Roach is a retired Texas Christian University adjunct English professor, author of nonfiction books, short fiction, and juvenile fiction, a folklorist, grassroots historian, rancher, and naturalist. Her writing has won three Spur Awards and the Carr P. Collins Prize. She is an active member of many organizations, including the Texas State Historical Association, the Texas Folklore Society, the Texas Institute of Letters, and the West Texas Historical

Association.

10.23.2016 Joyce Gibson Roach: Living and writing in the “Land of Rain Shadow"

Fort Worth author Joyce Gibson Roach is still blazing trails at eighty. The fifth-generation Texan and Texas storyteller will be inducted into the Texas Literary Hall of Fame in a special ceremony by the Friends of the Fort Worth Library at the Fort Worth Arboretum November 4. She has spun a lifetime of stories about West Texas, horses, cowgirls, and talking horned toads. She took time from her upcoming writing projects to participate in an interview with us by email.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Joyce, Your most recent book, The Land of Rain Shadow: Horned Toad, Texas, came out last year, when you were 79. This collection of short stories about West Texas has been widely praised for its craft. What does the phrase “The Land of Rain Shadow” mean, and could you describe this book in your own words?

JOYCE GIBSON ROACH: Rain Shadow is a meteorology term describing how dry and desert places are formed. Moisture moves up the east side of mountain ranges but is blocked on the west leaving the west side in the shade of moisture. West Texas and other arid places in the Southwest remain dry and always in need of rain. (“The litany of brown places is always supplication for rain, and the colloquy of praise is ever for it.”) The description identifies West Texas and Horned Toad, Texas, in Caballo County, an imaginary place in rural West Texas with a small population whose icon is a water tower and the people who have lived and endured there—still do.

The collection of short stories is dated, moving back and forth through time periods expressing how such an environment informs the characters and story lines. The first story, “In Broad Daylight,” centers on an election with only one candidate running for sheriff, Jesse Earl Putty, whose only platform is keeping bras on all the women, referring back to the beginning of the feminist movement when some women burned their bras. The Donald Trump–like character is outwitted and beaten by Joe Don Wheelright, who teams up with Annie Laurie Rogers to elect the first female sheriff in Caballo County. Two stories, “Just As I Am” and “Won’t Somebody Shout Amen,” reveal the effects of religion on youngsters who come through with a new spirituality not because of religious upbringing but in spite of it. Two other stories, “Promised Land,” and “The Day After Pearl Harbor,” reveal the home front during World War II from the viewpoint of those who never went to war. A Christmas pageant causes a riot when a backward ranch boy shows up using ranch language, sometimes used only on stubborn cattle and bankers, and improvising dialogue to welcome the Wise Men in The Worst Christmas Pageant Ever. “A Two Gun Man” features a youngster of mixed parentage who lives on a ranch with his father and whose only companions are the cowboys and Ma’am, who teaches him to read. Longing to shoot guns, the child practices in front of a mirror but plans to really shoot when he’s ready. Sneaking out to the outhouse, dragging various guns with him, something happens that causes him to shoot for real, the result of which is that he shoots Ma’am’s cat, which has to be scraped off the outhouse wall.

The last story, “Crucero,” reaches into the future from the past when a Negro man and wife end up in far West Texas on a Mexican ranch which raises horses and mules as well as cattle. They find emancipation and freedom there never known in their past. This story needed an historical connection to the years just after Pancho Villa days when there were still traditional horse ranching enterprises still going on in Texas, especially along the border. I failed to offer an explanation and to emphasize that haciendas were small villages unto themselves with little known about them outside their walls. I regret my lack because it would have made the story even more believable.

We’ve talked about your most recent book. What was your first book publication, and how did it come about?

My first book was The Cowgirls. I had finished a master’s degree and recognized that scholarly writing would never be my thing. My thesis was in medieval studies, and other scholars had pointed out [how] the world of knights and fair ladies approximated the western genre. A professor and friend, Mabel Major, asked me why I was so interested in the medieval world when my own back yard was immediate, in need of explanation and worthy of writing about. I recognized that kind of West in my hometown of Jacksboro—ranchers, horses, and a kind of female not accounted for in western literature. Pioneer women, yes—but cowgirls, as they were known, were cut out of a different piece of cloth. There was a family of three girls who were truly cowgirls, Ada, Jackie, and Mary Worthington. The cowgirl world was right under my nose.

I read through your vita on your website and was blown away by, first, your honors from prestigious writing groups and organizations and second, I was struck by your incredible work ethic. If you aren’t writing a book, you’re judging a contest, or editing a collection or teaching a class or presenting a scholarly paper. How was your work ethic formed?

I’m embarrassed to say that my writing worth ethic is not consistent. Don’t forget that what I’ve done, said, written is spread over fifty years. My first book came out in 1977. Articles and such were written first as speeches, papers given at Texas Folklore Society; later Texas State Historical Association and later still, the Philosophical Society of Texas. More books followed.

I know that many young women were influenced by your book The Cowgirls (1977), which in some ways was one of the first books of its kind to showcase the work ethic of the women on the range. What books did you grow up reading, and what inspired you to write The Cowgirls?

I was inspired to write The Cowgirls because no one had taken on that subject. I showed an outline and sample chapters to my mentor, best friend, and sternest critic, C. L. Sonnichsen, who told me I was onto something, but I wasn’t a very good writer. He was right. I sent the completed manuscript to Doubleday in New York. I received not only a rejection slip but a fairly long letter, the gist of which noted that if I was anybody with a “name” the publishing house would take it in a minute, but since I was a nobody they couldn’t use it.

That rejection smarted some, but I then went to Horseman Magazine, which I knew published a few books. They took it, did no editing whatsoever, published it with old-fashioned footnotes, and kept it in print through the magazine ads alone and didn’t drop it until 1988. UNT Press director Fran Vick reprinted it with a Barbara Whitehead cover and it’s been in print ever since. It was named a classic in the early 2000s and remains as print-on-demand today. As to what books I read: Mostly I read the Reader’s Digest. Go ahead and laugh. My town didn’t have much of a library. What I was reading in school was wonderful. “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and Julius Caesar were the biggies. The Bible was another source of reading. I won’t say it inspired writing because of the rich stories and Bible themes, but the imagery and speech patterns languaged my writing along with those my grandmother and my daddy.

How has publishing changed since you started?

Publishing in the ’60s and beyond held the Western in high regard. And it was a man’s world and male writers dominated the field. Nonfiction was often scholarly and there, too, men dominated. Eventually the genre didn’t sell and publishers stopped their Western publications. Other genres got interest—mysteries, crime, romance, and the like took more interest of the big publishers. Women gained ground in those categories. At least that’s what I think, although it may not have been that way from others’ perspectives. I was somewhat stuck between because I am above all things a folklorist. My writing has a lot to do with folk history, folk characters, more of the past than the present or future. Popular publishers found my work too scholarly; scholars thought it too popular. I’ve managed to find my way to publishing by working in more than one genre.

Who are some of the Texas writers you have known and collaborated with? Which Texas writers do you enjoy reading?

The writers I’ve known? Tom Lea, Elmer Kelton, Robert Flynn, Jim Lee, Sarah Bird, Judy Alter, Bruce Duffy, all Texans except for Duffy, who lives and writes in Maryland and is best known for The World As I See It, about the philosopher Wittgenstein, and is a classic on the New York Times list. I did collaborate with Ernestine Sewell Linck, now deceased, on Eats: A Folk History of Texas Foods. The book was her idea, and I supplied some of the text and recipes. The book won the TIL award for best nonfiction. I collaborated with Sara Massey on two juveniles about Texas women (accepted, not yet published). Sara died a few years ago just after submissions were made and contracts offered.

What are your three all-time favorite Texas books?

Dorothy Scarborough’s The Wind, Tom Lea’s The Wonderful Country, Willa Cather’s Death Comes For the Archbishop. That’s only three of many more I could have named.

You write a lot about West Texas. Where does West Texas “begin,” in your estimation? What makes it different from the rest of the state?

The West begins for me anywhere west of Fort Worth, beyond the Brazos River to El Paso and the Rio Grande, south of Amarillo to the Big Bend, to the coast and everything in between. The region comprises over half of Texas. It is an honest land; doesn’t deceive you with trees, bushes, or green. It is a brown place where even the plants, animals and human vocabulary go armed with stickers, blades, and thorns, fangs and horns, stinging words and fiery incantations. When times are bad there’s no way of leaving; when times are good, there’s no way I would.

What’s your writing process like? Do you write every day?

No. My writing is sporadic. I’m undisciplined. I’m more than fortunate to have mentors who instruct me with their writing, their work ethic, their interest in me: Phyllis Bridges, Fran Vick, Jim Lee, Bob Compton, Fred Erisman, Bob Frye. They help and accept me, warts and all, and inspire me to keep writing..

Congratulations on being inducted into the 2016 Texas Literary Hall of Fame. What’s next for Joyce Gibson Roach?

Two juveniles about Texas women—Spirit in Blue, about Maria de Agreda of Spain, under contract with Texas Tech Press, and The Woman Who Rode Redbuck, about Sally Skull, under consideration with TCU Press. Both were co-written with Sara Massey.

* * * * *

Praise for Joyce Gibson Roach's The Land of Rain Shadow: Horned Toad, Texas

“Joyce Gibson Roach is a legend. She has truly outdone herself with her new collection of stories about the place that made her who she is. It’s an honor to know her and to know this book.” —Sarah Bird, author of Above the East China Sea

“With these eight gems of short fiction, Joyce Gibson Roach captures the culture of West Texas with precision and authenticity. Roach’s characters speak the language of the folk and carry the values of small-town Texas. The gallery of characters, from high-toned women to cowboy ranch hands, along with young narrators with hidden dreams and complicated questions, provide a chronicle of West Texas that has both local color and universal application. This book is destined to be a classic of Texas literature.” —Phyllis Bridges, Cornaro Professor English, Texas Woman’s University

“I know the exceptional talent of this award-winning author and have read most of her stories as well as most all of her writings in other genres. This new collection contains an unpublished story—‘Crucero’—which I believe is one of the best she has ever written. It is a gem.” —Bob J. Frye, emeritus professor of English, Texas Christian University