Each week Lone Star Literary profiles a newsmaker in Texas books and letters, including authors, booksellers, publishers.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

Kay Ellington has worked in management for a variety of media companies, including Gannett, Cox Communications, Knight-Ridder, and the New York Times Regional Group, from Texas to New York to California to the Southeast and back again to Texas. She is the coauthor, with Barbara Brannon, of the Texas novels The Paragraph RanchA Wedding at the Paragraph Ranch.

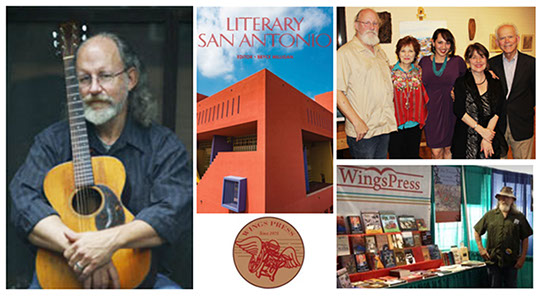

3.11.2018 Bryce Milligan crowns four decades of story and song in San Antonio with a long-awaited anthology

When a city celebrates 300 years of existence and an even longer tradition of diverse cultures, it takes a profound editorial vision to understand how those cultures have come together in the present. Author, editor, and musician Bryce Milligan definitely has the long view. It’s only fitting that we talked with him via email during the week of our Top Ten Texas Bookish Destinations coverage, to share with our readers what Milligan appreciates about literary San Antonio.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Bryce, I understand you were born in Dallas but have lived in San Antonio since 1977. What brought you to the Alamo City?

BRYCE MILLLIGAN: I met my wife in one of the only creative writing classes either of us ever took—at the University of North Texas—when we were both freshmen. Mary was from San Antonio, so when she finished her MLS a few years later, we moved here so she could take a job in the public library while I commuted to Austin to work on my MA. I’d had a fascination with San Antonio since childhood, which only deepened as I came to know the city better.

You were twenty-four when you arrived in San Antonio. In many ways, you and the city have grown up together. What was San Antonio like in 1977?

There were several independent bookstores. The most important was Rosengren’s, which was located on the bottom floor of the Crockett Hotel behind the Alamo. Florence Rosengren’s store was known throughout the country as an intellectually and culturally important place where writers gathered and readers found nirvana. As Robert Frost said, it was “the best of bookstores.”

There were plenty of used bookstores too. The best known of those was Brock’s, which occupied half of a city block downtown. Norman Brock had amassed close to a million books—so many that when part of a floor gave way, it was supported by a pillar of books in the basement. It’s hard to believe now that they let people down there, but intrepid book scouts like myself thought of it as a place to go treasure hunting. There were no chain stores then, new or used, so independents did well. On the other hand, there were no bookstores on the south and west sides of town, which is still true. We worked to change that, but with very limited and only temporary success.

The theatre program at Incarnate Word was the best in town, featuring Dublin’s Abbey Theater veterans Maureen Halligan and Ronnie Ibbs. After an evening of classic Irish drama, which they produced often, patrons would retire across the street to Earl Abels for coffee and pie and conversations.

The UTSA main campus was a very long way from anywhere, and it was surrounded by miles of wildflowers. There were very creative writing classes in town. Robert Flynn’s class at Trinity was thought of very highly. John Igo was a loveable curmudgeon even then, and he mentored young writers at SAC. He also had a popular “grammar gripes” segment of a popular morning show on WOAI.

The Chicano literary scene was quite active and very interesting as young writers like Carmen Tafolla, Evangelina Vigil, Inés Hernandez-Tovar (all under the tutelage of Angela de Hoyos), Jesse Cardona, Reyes Cardenas, Max Martinez, José Montalvo, Nephtalí De Leon were just getting started. San Antonio’s only Floricanto literary festival was that year, held in half a dozen locations but mainly at the Mexican American Cultural Center and Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. The Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center and the Esperanza Peace & Justice Center were both still dreams.

There is a lot to say about that time because so much was being planned and invented that would only flourish in the ’80s.

The Blue Hole and San Pedro Springs ran freely, but the river was badly polluted. Some Westside streets were still unpaved. An old vegetable seller still pushed his wooden-wheeled cart up and down Guadalupe Street. COPS, organized and trained by Michael Kruglik, who had been trained by Saul Alinsky, were busy forcing San Antonio businesses and the city itself to cure their racist policies and practices. Rosie Castro had run for city council earlier in the decade, and Henry Cisneros had just been elected. Otherwise, there were very few Chicano elected officials at the city or state level.

In short, like almost every other decade of every other century, it was the best of times and the worst of times for those who had to live through them.

You are a musician and songwriter — even performing in clubs in Dallas when you were still in high school. When did you choose to try other forms of writing, such as poetry and fiction?

Actually, I cannot remember a time when I was not telling myself stories and playing with rhymes. I remember making up new lyrics to the songs I heard on a homemade crystal radio late at night when I was in early elementary school. We had a good public school with a good library, and an orchestra program that started in first grade (I played cello and trumpet in grade school). My father played banjo, an uncle was a harpist, both grandmothers played piano and painted. We went to the Baptist church three times a week and sang in countless choirs. I started slipping out of the house to go to a folk club called the Rubaiyat when I was sixteen, and was soon playing occasional opening sets. Older folksingers like Townes Van Zandt, Michael Martin Murphey, Ray Wylie Hubbard, B. W. Stevenson, and others generously critiqued my songs — which constituted the best creative writing “classes” I ever had. Basically, I grew up in a cultural hothouse. It wasn’t always high culture, but certain flowers were bound to blossom, so to speak.

You were the book critic for the San Antonio Express-News from 1982 to 1987, and for the San Antonio Light from 1987 to 1990. What brought you to book criticism? How would you characterize the current state of book criticism in Texas's newspapers and beyond?

I was working at Rosengren’s and we were pretty poor. Roger Downing, an editor at the San Antonio Express-News, put a note up on the bulletin board saying that he had free books for anyone who wanted to try reviewing. Free books! I dove in and in a couple of months they gave me a column—and almost free rein. I loved small press publications and so I reviewed a lot of “early” Chicano, Black, and Native American books, and a lot of poetry. Most newspapers and journals didn’t review these, so I developed a sense of critical responsibility about what I was doing.

I was also editing a small press literary magazine in the ’80s—Pax: A Journal for Peace Through Culture and, with Robert Bonazzi, Vortex: A Critical Review. It became clear to me and to Sandra Cisneros, whose House on Mango Street I’d just reviewed, that we needed to do something to promote this diverse wonderland of literary creativity. My wife, Mary, and I had put on a small literary festival and book fair at the New Age School (now the Circle School), where we’d had Sandra read, so Sandra and I created the Annual Texas Small Press Book Fair, modeled on that little school fair. Sandra was running the Guadalupe’s literature program and I was editing The city gave us a grant of a whopping $500 to run it. Eventually that evolved under Rosemary Catacalos into the San Antonio Inter-American Book Fair. I was asked to take over the program there again in 1994 and ran the GCAC literature program and its book fair until 2001. I also created an academic conference, Hijas del Quinto Sol, co-sponsored by St. Mary’s University. That morphed into the Latina Letters conferences, which is now Las Americas Letters. We did some other inventive stuff, like a PBS-televised poetry slam for high school students.

Current newspaper book coverage—well, in San Antonio we are blessed to have a two-page book spread every Sunday in the Express-News, which includes a regular poetry column by Robert Bonazzi, and a poem a week by local poets. That makes it almost unique in the U.S. The Dallas Morning News has excellent book coverage as well, although it devotes less space to it than it once did. David Bowles writes fine reviews for the McAllen Monitor. On the other hand, we’ve lost a lot of coverage that was very valuable—for example, the Texas Observer is down to reviewing one book a month. Texas Books in Review is good but has a limited readership. For a small press like Wings, it is very difficult to get reviews in general, as the trade journals like Publishers Weekly and Library Journal pay scant attention now unless you spend serious advertising dollars with them. Wings has been in business for 43 years, and to my knowledge the Houston Chronicle has reviewed exactly two Wings titles, one of them by a Chronicle editor. In 40-plus years, Texas Monthly has reviewed one Wings title, Black Like Me, when we published the 50th anniversary edition of that American classic.

I have to say, were it not for online reviews like Lone Star Literary Life, getting the word out about new books in our region would be a lot more difficult. Obviously there are a lot of book bloggers out there now, but it is hard to tell which ones have a lot of readers. I regularly send out 80 to 100 review copies of a book, but there are literally thousands of bloggers across the country, so it’s a new world.

For more than four decades, Wings Press has published a remarkable number of books — more than 200 titles. You have published poets laureate from six different states and the first two Latina poets laureate of Texas. But how did you come to own Wings Press?

That’s a long story, and one I’ve told often. The short version is that Joanie Whitebird, who started the press in 1975 with Joe Lomax, had fallen on hard times. Joanie had just published my book Working the Stone in 1993 when the press went belly-up. She sold it to me for a minimal amount but required a blood promise that I’d keep it going. She liked what I’d done with and Vortex and at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center with the book fairs. So we split our palms in the back yard and I went to Houston to pick up the little stock that was left—mainly chapbooks by Vassar Miller, Naomi Nye, Robert Peters, and a few others, as well as Townes Van Zandt’s songbook, For the Sake of the Song. The first book I published, in 1996, was This Promiscuous Light, a small anthology by young San Antonio women poets, most of whom I had met while working as an artist in the schools.

Your most recent project is Literary San Antonio from TCU Press, a perfect complement to San Antonio’s 300th Anniversary celebration. You, are, of course, the perfect person to edit this book. Can you tell our readers about that book and what’s it like being in San Antonio for its tricentennial?

First, thanks to Michelle Newby for her delightful review of Literary San Antonio in Lone Star Literary Life [read the 2.25.2018 review here]. Several years ago, TCU Press began publishing their Literary Cities series. Most of the editors, I assume, were academics who could rely on a paid sabbatical or two to get the editing done, but, lacking that “luxury,” I took a little longer. I started gathering materials about eight years ago, and soon had a manuscript stack of a couple of thousand pages. It took a good deal of winnowing to get that down to a more manageable size, and then TCU Press wanted it even smaller . . . . It became evident a couple of years ago that the book should come out during the Tricentennial.

Literary San Antonio is a collection of writing about San Antonio, by San Antonio writers — poets, fiction writers, playwrights, journalists, historians, political writers, and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century travelers. It covers three centuries of writing done in this place. The depth and diversity of San Antonio’s culture/cultura, and the charm of its cultural ambience, have been remarked upon since the middle of the nineteenth century. This region has been a cultural crossroads for a very long time, even before the Spanish arrived. It was a place rich in water and game, a place where northern tribes and southern tribes met to trade everything from peyote to buffalo hides, from flint to pottery. Soon after the Spanish arrived, it became the nexus of travel both north and south and from the coast to New Mexico. Other immigrant groups arrived to make the pot even more diverse. It was inevitable that literature would arise out of all that. The first printing press arrived here in the early 1820s, and the first Texas novel was written here in the late 1830s. The first bookstore/stationer’s shop opened in 1854 — Julius Berends’s Old Curiosity Shop. Visiting writers came and wrote about this place — Frederick Law Olmsted, Sidney Lanier, O. Henry, many others—which gave it a kind of exotic literary charm.

Meanwhile, Spanish-language publishing began to thrive in the 1890s as revolutionary fervor built in Mexico and intellectual exiles started to arrive. A book entitled La Sucesión Presidencial en 1910 appeared in 1908, published in San Antonio by the Flores Magón brothers. Its author was Francisco Madero. Two years later, Madero published his Plan de San Luis Potosí, calling for an armed rebellion to begin on November 20. Which it did. It is important to reiterate that this book, which literally called the Mexican Revolution into being, was written and published in San Antonio, printed on Santa Rosa Avenue.

This history is so rich, and the multicultural, multilingual environment so alluring, that it was inevitable that creative writers were drawn to the city. Here’s the last paragraph of my introduction to Literary San Antonio:

This city, with its winding, still-sleepy river and its story-shrouded springs, its ancient acequias and missions—now acknowledged as valued “world heritage” sites—its sacred battle grounds and historic military forts and bases, its several unique neighborhoods and barrios that have produced and been celebrated by generations of writers, its rich heritage of heroism and revolutionary passion, its endlessly celebratory ability to revel in its multiracial, multiethnic, multilingual roots and branches … this city is a good place to write.

I stand by that.

Wings Press is one of the most inclusive presses — ever. Sixty percent of your authors are female. You publish authors from all over the world. But how would you describe your overarching approach to publishing, and how has it changed over the years?

My approach to publishing hasn’t changed a lot. I publish what I see as “necessary work” within a literary context. I’ve done some nonfiction — memoirs like María Berriozábal’s Maria: Daughter of Immigrants, or Robert Flynn’s Burying the Farm, or Carmen Tafolla and Sharyll Teneyuca’s children’s book, That’s Not Fair/No es justo, about labor leader Emma Tenayuca, but mostly I’ve focuses on poetry and fiction that I find culturally important, aesthetically inventive, and politically open-minded.

Wings Press is not a non-profit, but it has a mission statement that runs in every book: “It is the mission of Wings Press to publish the finest in American writing — meaning all of the Americas — without commercial considerations clouding the choice of what to publish or not to publish. Wings Press produces multicultural books, chapbooks, ebooks, and broadsides that, we hope, enlighten the human spirit and enliven the mind. Everyone ever associated with Wings has been or is a writer, and we know well that writing is a transformational art form capable of changing the world, primarily by allowing us to glimpse something of each other’s souls. Good writing is innovative, insightful, and interesting. But most of all it is honest.”

Four of the past six Texas poets laureate have been from San Antonio. What is it about San Antonio that produces such wonderful poets?

Good question. There are excellent poets all over Texas and the Southwest, too often ignored by the rest of the country. San Antonio is enjoying a confluence of cultural and political streams that have allowed and encouraged a thriving literary culture. We have good creative writing programs at UTSA and Our Lady of the Lake, good multicultural studies programs, an excellent literary arts center in Gemini Ink with a good annual writing conference, a top-notch public library that is fully involved in the literary community, plus UTSA’s important San Antonio Authors Collection, a newspaper that pays attention to local writing, journals like Voices de la Luna, university creative writing magazines, and the Esperanza Peace & Justice Center’s La Voz, and others. And the city’s Department of Arts and Culture has been very supportive. San Antonio created the state’s first city poet laureate position, and it is not just ceremonial, but provided with funding to enhance and expand the awareness of poetry. And there is Wings Press. Plus, maybe there’s just something in the water!

You have been a folk singer, a poet, a novelist, an essayist, a critic, a teacher, an editor, and a publisher, but perhaps my favorite skill from your vita is that you are a luthier. For our readers not familiar with this role, will you tell them what the job entails?

My uncle Sam is a harpist and harp maker, so I grew up with the notion that making musical instruments was a physical kind of poetry. I was apprenticed to a guitar restoration guy, Don Berry, in Dallas when I was in high school and I worked with a flute maker, Mr. Kilpatrick, at the University of North Texas for a year. But I would not call myself a true luthier—a maker of stringed instruments. A true luthier is an artist of the highest order, bringing music out of wood, metal, glue, and imagination and insight. I’ve made dulcimers and drums and guitars, but mainly I like to restore and play older instruments. It is not something that I have much time to do anymore, but it is very therapeutic for my writing, so I often work with wood, stone, or earth when the muse is not being especially cooperative.

As the ultimate connoisseur of the San Antonio literary and cultural scene, could you recommend three places that every literary aficionado should visit in San Antonio?

That would be a very idiosyncratic recommendation. Like Stephen Crane, Sidney Lanier, O. Henry, Naomi Nye, Rosemary Catacalos, Ricardo Sánchez, Carmen Tafolla, Jenny Browne, Carol Reposa, and a host of others, I would say just walk the city and listen to the voices, listen to the water, listen to the trees, listen to the history around you.

Thank you for sharing your deep well of knowledge, Bryce. I would like to close out this interview for our readers with a quote from the media that brings your varied roles full circle. In 2016, Huffington Post wrote,

“Author of numerous works of poetry, fiction and theatre, a legendary editor and publisher in Texas, Milligan is a literary master, a linguist and luthier of ancient languages and songs, whose new work places him and his Texas landscape in the front ranks of our nation's most respected literary figures.”

* * * * *

Praise for Bryce Milligan's LITERARY SAN ANTONIO

“It takes a rare combination of hubris, erudition, faith in the inspiration of the muse and a profound appreciation for local culture and history to undertake such an ambitious project as an anthology of three centuries of writing in and of San Antonio.” —San Antonio Express-News

“Literary San Antonio rolls on for more than 400 pages, and it is compelling reading: poetry, journalism, fiction, drama, history. In large part, this is because of the literary tapestry created by all those different voices.”

—Dallas Morning News

“Literary San Antonio offers many gems, an invaluable anthology and addition to Texas letters. I can’t imagine a better way to celebrate San Antonio’s tricentennial year.”

—Lone Star Literary Life

* * * * *